Interview: James Brogden

James Brogden’s horror and fantasy stories have appeared in anthologies and periodicals ranging from The Big Issue to the British Fantasy Society Award-winning Alchemy Press. His latest novel The Plague […]

James Brogden’s horror and fantasy stories have appeared in anthologies and periodicals ranging from The Big Issue to the British Fantasy Society Award-winning Alchemy Press. His latest novel The Plague […]

James Brogden’s horror and fantasy stories have appeared in anthologies and periodicals ranging from The Big Issue to the British Fantasy Society Award-winning Alchemy Press. His latest novel The Plague Stones is out now from Titan Books (read our review here), and continues his run of strong genre tales that includes Hekla’s Children and The Hollow Tree. He chatted with Paul Simpson about the three novels…

James Brogden’s horror and fantasy stories have appeared in anthologies and periodicals ranging from The Big Issue to the British Fantasy Society Award-winning Alchemy Press. His latest novel The Plague Stones is out now from Titan Books (read our review here), and continues his run of strong genre tales that includes Hekla’s Children and The Hollow Tree. He chatted with Paul Simpson about the three novels…One thing that struck me with Hekla’s Children was how many different genres you hit with that!

It was a little bit of a mishmash.

Was that the nature of the story you wanted to tell – your protagonists were going through a different sort of curve than the usual?

Again, it was deliberate to an extent because I’m a massive fan of Graham Joyce and Robert Holdstock, and a lot of their writing is very fuzzy in being able to pin down what sort of genre it is; Sarah Pinborough’s Dog-Faced Gods trilogy – I thought that was a fantastic blend of different genres. There was an attempt to write something which had that kind of mythical, fantastical underpinning to it but which didn’t rely too much on the predictable tropes. It was a conscious decision.

Again, it was deliberate to an extent because I’m a massive fan of Graham Joyce and Robert Holdstock, and a lot of their writing is very fuzzy in being able to pin down what sort of genre it is; Sarah Pinborough’s Dog-Faced Gods trilogy – I thought that was a fantastic blend of different genres. There was an attempt to write something which had that kind of mythical, fantastical underpinning to it but which didn’t rely too much on the predictable tropes. It was a conscious decision.

Was there a pushback editorially against mixing so much?

Was there a pushback editorially against mixing so much?

I think they were very generous; they got the sense of what I was trying to do and [my editor] Miranda [Jewess] was very keen on helping me make it work. One of the problems I had in writing it was this idea of the Un, the spirit realm which the four children get sucked into – she made me pin it down. What exactly is this place? Is it back in time? Is it the spirits of dead people? How exactly does this place work so it’s got some kind of consistency to it? I was all timey-wimey wibbly-wobbly – it’s this other place, it doesn’t have to have rules, but she was, “Yes it does have to have rules otherwise the reader won’t get it.”

And it’s always clear to anyone when the author doesn’t know what the hell they’re doing, no matter how well edited.

When I’m feeling masochistic and read the negative reviews there are two things that people pick up on – there’s one bit where the male protagonist is travelling through Un, he has a relationship with another guy, and people pick up either that “that wasn’t telegraphed earlier in the book so that’s not consistent?” or “how can he just change?” And the point is he’s in this other realm; things do change and they are fluid, so I don’t have much patience with that one.

The other one is that the focus of the story changes halfway through – you start off thinking that the main character is the male, and halfway through it becomes one of the female characters who carries through the second half. That was very deliberate, because the whole point of the male character, the whole weakness and flaw that causes his downfall is that he’s too full of his own self-importance. Everything is about him. I wanted to make that point of destabilizing the novel, where the reader gets halfway through and goes, “Where’s he gone?” It’s not about him now, it’s about her now and I wanted to make that the point of the novel. That’s one of those things which people think either works or they really hate – they say it’s a book of two halves, it doesn’t hang together or they say I shifted the perspective there.

There’s a late 90s movie called The Sixth Day – Arnie as a clone – where it takes about 45 seconds for your sympathies to switch from the person we originally take to be the hero. That’s a neat trick to pull off.

There’s a late 90s movie called The Sixth Day – Arnie as a clone – where it takes about 45 seconds for your sympathies to switch from the person we originally take to be the hero. That’s a neat trick to pull off.

It’s like those series when what you think to be the case all the way along turns out not to be the case or indeed the actual opposite of the case.

Moving onto The Hollow Tree, was there a conscious effort on your part to do something different?

I had started planning and drafting The Hollow Tree while Hekla’s Children was still doing the rounds so it wasn’t in response to reviews; I knew I wanted to do something on a smaller scale, a bit more domestic. Hekla is epic in terms of scale and I wanted to do something to bring it down to one person, her family, her background, and make it a bit more personal.

During the drafting did you find you were wanting to bring in more “reality” to the story and it wasn’t the way the characters and situations were taking it?

During the drafting did you find you were wanting to bring in more “reality” to the story and it wasn’t the way the characters and situations were taking it?

I tried to incorporate as much of the detail of the actual Bella story as I could into the fictionalised version of her as Mary in the book. Fortunately there’s not a huge amount of material knowledge about her to be contradictory: there’s a lot of stuff about the subsequent police investigation and the attempt to forensically test the remains using the limited technology that they had in the 1940s. I [originally] wanted to maybe deal with the police investigation a little more to ramp up the thriller aspect of it, but I realised that that wasn’t really what the story was about. I wasn’t actually interested in trying to pin down the reason or the identify of the woman – because that’s what everything that has been written about her has tried to do (“Who’s the woman in the tree?”). For me is not who she actually was but what the different stories about her tell us about ourselves and our own preoccupations with murder mysteries and kidnapped women and those sorts of things.

The story is far more about Rachel and her healing – her acceptance of ghosts – and a springboard into another story…

I’ve left it partially open for a sequel if there’s anything left to be told. The character of Rachel, she didn’t start off having any connection to the figure of Mary beyond her ability to reach into the netherworld, but it then made sense to give it more emotional punch for her to be related to the dead woman. It came to me in the form of a really bad pun – when I started writing about families and I knew the title was going to be The Hollow Tree, I realised it was the family tree that was hollow. It’s a physical tree and a symbolic tree. A little lightbulb moment!

It’s about families and the way people muck in together and the promises they make to each other and the compromises they make with each other and the mistakes they make trying to protect each other.

I had a period where I couldn’t use my hands after various operations, and as a keyboard player that evoked a lot of the emotions that Rachel felt – what research did you do for that?

Lots of YouTube videos – and when you start Googling videos about amputations, you have to be very careful about how you word it – and reading a lot of first-hand accounts about how people coped. There was a documentary on Channel 4 when I was roughing it out, a father who had a bacterial infection or something and lost most of his face, and his limbs. It followed his ability to get rehabilitated and took you into his feelings of how he was going to cope with the trauma he found himself in, and wondering how the hell I would feel or cope with losing part of a limb. Much as I’m sorry to bring back memories, it’s nice to know it feels authentic.

Lots of YouTube videos – and when you start Googling videos about amputations, you have to be very careful about how you word it – and reading a lot of first-hand accounts about how people coped. There was a documentary on Channel 4 when I was roughing it out, a father who had a bacterial infection or something and lost most of his face, and his limbs. It followed his ability to get rehabilitated and took you into his feelings of how he was going to cope with the trauma he found himself in, and wondering how the hell I would feel or cope with losing part of a limb. Much as I’m sorry to bring back memories, it’s nice to know it feels authentic.

I didn’t want it to be full of “oh my life is doomed”. I figured people are stronger than that, and deal with things with a black sense of humour, hence the silly little things thrown in there like joking with her husband about having a sex toy attached to it, puts a slot for her iPhone – the human touches which I think people would do.

The most recent book is The Plague Stones – how does that differ?

The most recent book is The Plague Stones – how does that differ?

Someone did once say, “Brogden does like taking his characters to other planes of reality”, which I’ve kind of done in every book I’ve written so far to some point. There’s a love of portal fantasy in there; I love my Narnias.

The Plague Stones is again a sort of folk horror. It’s about a village that was a village in medieval times, and now it’s incorporated as part of a large city but they have a ritual of the Beating the Bounds, where they go round the parish boundaries. They still have that ritual going on and they have to do it every year, because if they don’t horrible things will happen.

I know of at least one Sussex parish where people definitely still believe that…

I love that kind of tradition, the idea that those kinds of really old traditions are still taking place in the most modern cosmopolitan settings. You have this village that in the 14th century at the time of the Black Death refused to help their neighbours – so the spirits of the neighbours who were betrayed and left to die, if the Beating the Bounds is not maintained, those vengeful spirits will come into the village and wreak their revenge.

It’s still touching on the elements of what people are calling folk horror, but it’s more a straight up horror novel. There’s no shuffling off into alternate realities – it’s going to be very straight English countryside Gothic with vicars with dark secrets and little old ladies in their tea rooms. A little Royston Vasey – I love that Hammer Horror genre and push a few of those buttons this time.

What was the most challenging part of the writing of The Plague Stones?

What was the most challenging part of the writing of The Plague Stones?

Trying to figure out how to introduce the antagonist’s Achilles Heel given that she’s been haunting the village for nearly seven hundred years, during which time the locals have tried literally everything to get rid of her, without making it seem too much of a deus ex machina. Trying to make it all fit logically with what the reader knows of her past. I almost wrote myself into a corner by making her so tough.

You mention learning a lot more about medieval history during the edit process – what bits specifically did you need to delve into more?

You mention learning a lot more about medieval history during the edit process – what bits specifically did you need to delve into more?

It was mostly background stuff, like what age Hester could reasonably expect to be married, how her father’s job as village reeve would have worked, religious reactions to the plague etc. I’m fortunate in having such thorough and knowledgeable editors who could point me towards those things, because then I made serendipitous discoveries like the use of tally sticks which gave me both a useful plot device and a nice symbol of the ‘reckoning’ that Hester wants.

The Christian material is (I know from my own research on this) accurately portrayed – did you talk to Deliverance Ministers?

I’m glad that what I’ve written rings true! I didn’t discuss it with any actual ministers, but I do have a good friend who’s a Religious Education teacher who gave me a lot of useful information. Teachers are such useful people to know…

As with the other books, was there a specific image or sequence in the story that inspired it, or something outside?

As with the other books, was there a specific image or sequence in the story that inspired it, or something outside?

It’s more like the result of a lot of unrelated ideas swilling around in my brain until some of them start to make connections. I knew that I wanted to do something with a protective stone circle but put it in an urban context, to mix up the idea of “folk horror” having to be set in rural locations because cities have their folk traditions too. Then Brexit and Grenfell happened and I knew that it had to say something about how we treat the Other in our communities. Add a dash of classic 80s horror The Fog, a housing development appearing in the fields near my home, and a pinch of Time Team, simmer for six months and you’re done.

Out of interest, did you ever see the TV series Survivors? The ending of this seems a direct inversion of the title sequence of that (or pure coincidence).

Out of interest, did you ever see the TV series Survivors? The ending of this seems a direct inversion of the title sequence of that (or pure coincidence).

I was actually thinking of something between 12 Monkeys and the plane sequence from World War Z when I wrote it, but yes, that’s even better. From my limited research I believe that most experts agree that if a pandemic is going to occur, it’s going to be the airlines that carry it.

The Plague Stones is available now from Titan Books

Thanks to Lydia Gittins and Sarah Mather for their help in arranging this interview

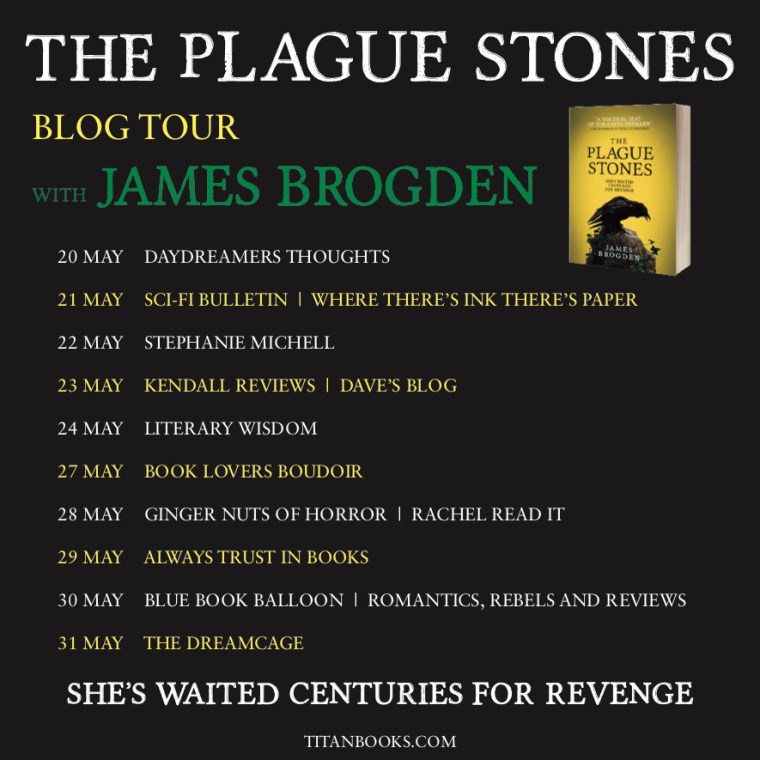

Check out the other stops on the blog tour: