by Richard Marson

by Richard Marson

Miwk Publishing, out now

A revised edition of JN-T: The Life & Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner…

Given that the newly retitled biography of JN-T is an opportunity to bring the original book into print, accompanied by an addendum to the original, it’s appropriate to start with Brian J. Robb’s review of the 2013 original (or skip to the bottom for a look at the new material):

The life story of 1980s Doctor Who producer John Nathan-Turner, warts and all…

This book created something of a minor media storm when one chapter in particular made the front pages of several tabloids. This attention, however unsavory, was inevitable as former Blue Peter editor Richard Marson has produced a horribly honest account of the life and times of Doctor Who’s most controversial producer.

Nathan-Turner (or JN-T, as he was known to fans) was put in charge of the show in 1979, immediately setting out to reinvent it for the 1980s. He was hailed as the fans’ producer, and he opened access (for good and ill) to the show like no producer before or since.

Nathan-Turner (or JN-T, as he was known to fans) was put in charge of the show in 1979, immediately setting out to reinvent it for the 1980s. He was hailed as the fans’ producer, and he opened access (for good and ill) to the show like no producer before or since.

As someone on the fringes of all that—from surreptitiously attending studio recording sessions in Television Centre and later regularly meeting JN-T in the Bush pub near Union & Threshold House (where the Who production office was based) when editing DWAS newsletter Celestial Toyroom—I was privy to a lot of sometimes unbelievable stories, many of which are now confirmed in this book.

Marson is in an ideal position to write this, as he knows only too well the inner workings of the BBC and what it is like to fall from grace within the institution. Like JN-T, he was in charge of a national television institution (Blue Peter) during turbulent times. His insight and contacts within the BBC have provided him with a unique filter through which to tell JN-T’s story. He was also a writer for Doctor Who Magazine, so was heavily involved in the upper echelons of Doctor Who fandom during the 1980s. This combination gives him a unique personal perspective on this story. He has obtained interviews with the majority of those who were around at the time, from on-screen talent to behind-the-scenes folks at Television Centre. Friends and foes of JN-T alike have opened up—and then some—about him and his work.

And what a story it is. Doctor Who fans know much of it, if superficially, but this book fills in JN-T’s early years and his post-Doctor Who decade: he drank himself to death rather young at just 54, just over ten years after he’d left the BBC. These final chapters are poignant, telling of a man who was a production whiz when it came to managing finance and resources within an institution like the BBC, but who was simply not equipped creatively to thrive when cast adrift in the independent production sector of the 1990s.

And what a story it is. Doctor Who fans know much of it, if superficially, but this book fills in JN-T’s early years and his post-Doctor Who decade: he drank himself to death rather young at just 54, just over ten years after he’d left the BBC. These final chapters are poignant, telling of a man who was a production whiz when it came to managing finance and resources within an institution like the BBC, but who was simply not equipped creatively to thrive when cast adrift in the independent production sector of the 1990s.

The bulk of the book covers his decade running Doctor Who, with the many ups-and-downs, the feuds (such as with script editor Eric Saward), and the successes. JN-T was clearly a great promoter, perhaps the best PR man the show ever had, but he was not a story guy—a line producer rather than a showrunner, in today’s parlance. He left the creative side up to others, allowing Andrew Cartmel, the final script editor on the classic show, to innovate while he concentrated on marshalling the show’s meager resources to best advantage. The cancellation crises of 1985 and 1989 are recounted in insider detail like never before, as are some of the more interesting financial aspects of the series production.

The most controversial elements of this book (and those that in these post-Jimmy Savile days led to those tabloid front pages) are the stories of sexual misconduct. JN-T was an ‘out’ gay man working in an environment where that was not a problem (in fact, Marson suggests that in some respects it was a positive advantage). One of the problems with the producer getting so closely involved with the fans (alongside its effect on the creative direction the show took, with ever more returning fan-pleasing monsters and characters) was that this spilled over into the sexual arena too. Prominent fans—among them Ian Levine—traded sex for access to the show’s inner workings. As an often-controversial figure in fandom, Levine is at least to be congratulated for coming clean about his involvement with this aspect of JN-T’s tenure. Marson also includes his own unpleasant experiences here, in the interests of full disclosure. To those blissfully unaware of all this, it will make for disturbing reading. For those around at the time who may have had an idea or two of just what was going on, it’ll confirm a lot of long-standing rumours. It is, however, just one aspect of a larger, even more troubling tale.

Marson also makes it clear that towards the end of the 1980s Doctor Who was allowed to die of neglect by the BBC. To drama head Jonathan Powell and others at the BBC it was an irritation, but they couldn’t justify getting rid of it as it was a reliable slot filler that cost little money (thanks to considerable financial input from BBC Enterprises). The problem was that no one was interested enough to make the show any better, by perhaps instituting a new production team—a problem compounded by the fact that no-one wanted to take it on, so low was the regard for the show within the BBC drama department. Running it against Coronation Street (ironically, JN-T’s favourite show) resulted in the drop in ratings that finally justified taking it off the air.

Marson also makes it clear that towards the end of the 1980s Doctor Who was allowed to die of neglect by the BBC. To drama head Jonathan Powell and others at the BBC it was an irritation, but they couldn’t justify getting rid of it as it was a reliable slot filler that cost little money (thanks to considerable financial input from BBC Enterprises). The problem was that no one was interested enough to make the show any better, by perhaps instituting a new production team—a problem compounded by the fact that no-one wanted to take it on, so low was the regard for the show within the BBC drama department. Running it against Coronation Street (ironically, JN-T’s favourite show) resulted in the drop in ratings that finally justified taking it off the air.

JN-T was equally trapped by the show, unable to leave it (as that would probably lead to cancellation), but not offered anything else as one of the last BBC staff producers (despite submitting a plethora of ideas to his bosses for new shows, most of them admittedly rather poor). He simply couldn’t escape it, and most of the second half of his decade in charge was the work of a man who clearly didn’t want to be there anymore.

There are villains in this book, key among them Powell (who admits his own management failure to tackle the ‘problem’ of Doctor Who) and, perhaps, the fans whose complaints drew attention to the show’s failing and so contributed in part to its eventual end. However, the biggest villain of the piece is by far JN-T’s partner Gary Downie. He is depicted throughout as one of JN-T’s worst influences, and the driving force behind their sexual exploitation of fans and others. Even so, when the book gets to their later years, and especially after JN-T’s death, it is possible to even feel a little sympathy for him. Not much, but some.

This is at times not a pleasant story, but it is a necessary one. It is unlikely there’ll ever be a TV movie chronicling the 1980s behind-the-scenes story of Doctor Who like the one on the 1960s, An Adventure in Time and Space. Instead, The Life and Scandalous Times of John Nathan-Turner will have to suffice: it is a page-turner of epic proportions that sheds new light on the period and the people involved. In that respect, it is unlikely ever to be bettered.

Verdict: A frank page-turner that finally puts John Nathan-Turner’s controversial stewardship of Doctor Who in a much-needed larger context, 9/10

Brian J. Robb

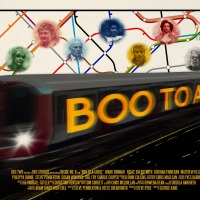

As well as an appropriately garish cover courtesy of Andrew Skilleter, the new edition contains a number of new photos from across JN-T’s life, as well as the aforementioned “Addendum: Eyes and Teeth”.

This is made up of extracts from assorted diary entries, emails and letters by, from or to author Richard Marson, chronicling the chronology of the book’s creation. It’s 66 pages long – which is about a fifth of the length of the original – and, I suspect, is likely to raise as many eyebrows as the biography that precedes it. The problems that Marson faced in getting the book to print are recounted honestly and a number of people don’t come out of it that well; likewise, the book’s reception before and after publication is discussed (and some people really don’t come out of that bit well!).

There’s plenty of praise recounted from those whose lives intersected with JN-T, who gave Marson invaluable help with the book, and Marson is frank about how he feels about others, particularly those who came at the book with what he sees as preconceived ideas or agendas. Does it give any more insight into JN-T? No, not really at all. Does it provide insight into Marson himself and some of those people (such as Ian Levine) who may only be “names” to many fans? Indubitably. It’s also an interesting snapshot of the BBC, and the way the institution is regarded, in the post-Savile era.

Paul Simpson