Feature: Dune: The Weltanschauung of Dune

Stewart Hotston casts a critical eye over Denis Villeneuve’s Dune… I’m going to start by saying Dune is a masterpiece. One of the most accomplished science fiction films I’ve ever […]

Stewart Hotston casts a critical eye over Denis Villeneuve’s Dune… I’m going to start by saying Dune is a masterpiece. One of the most accomplished science fiction films I’ve ever […]

Stewart Hotston casts a critical eye over Denis Villeneuve’s Dune…

Stewart Hotston casts a critical eye over Denis Villeneuve’s Dune…I’m going to start by saying Dune is a masterpiece. One of the most accomplished science fiction films I’ve ever seen, not to mention one of the best adaptations. What the director, Denis Villeneuve, together with his co-writers Eric Roth and Jon Spaihts, the composer Hans Zimmer, the cinematographer Greig Fraser, have achieved is something profound and wonderful. At times slow moving but never less than completely self-assured, beautiful and measured, this film will stay with me for a long time to come.

Alongside Arrival and Blade Runner 2049, Villeneuve has shown not only that he’s a master of the form but that he can and will create subtle, intelligent films that subvert expectation and he’s fine if you don’t get it (as many people didn’t with his exploding of the concept of male privilege in Blade Runner 2049).

In this piece there are several things I’m not going to do. Firstly, I’m not going to compare this to the other Dune films or attempts to adapt Frank Herbert’s book for the screen. I’m also not going to talk overly about Herbert’s original text.

I’m not interested in those comparisons, and I haven’t got time for people who can’t understand what the word adaptation means.

I’m also not really going to talk about the film as a review. Others have done that well enough. There are many things in Dune worth talking about and if this isn’t to be a ten thousand word essay then I’m going to stick to one thing: Dune’s Weltanschauung, which is really just a fancy word for the philosophy of Dune’s world, how it sees both itself and the world within which it exists.

Dune is, ostensibly, about a desert world called Arrakis on which an important product called Spice is found. Spice literally makes transport possible and without it the entire galaxy would grind to a halt. So far so much a story about oil in Arabia, yeah?

Dune is, ostensibly, about a desert world called Arrakis on which an important product called Spice is found. Spice literally makes transport possible and without it the entire galaxy would grind to a halt. So far so much a story about oil in Arabia, yeah?

We need to stop that right now because it comes bound up with too much of our own baggage about how the world works and most of that baggage is seen from the point of view of countries who have, in living memories, been imperial powers themselves.

We kid ourselves when we think we’re post-colonial in our thinking. We are only post-colonial in our thinking in that we acknowledge we Europeans don’t have empires any more. Most of us barely know when, how or why those empires deflated and we certainly don’t understand the economic and cultural imperatives which drove our societies to first create those empires and then sustain them in the face of ongoing, persistent (if frequently conflicted and nuanced) resistance from local populations.

The list of what we don’t know about our own histories is long and, honestly, deeply contested as there are legacies which are so recent those vested in seeing themselves as good people cannot bear to be questioned by those who would advance counter narratives. Just this week I’ve had to call out someone who should know better for suggesting the intentional genocide visited upon indigenous Americans was equivalent to what those same peoples did to one another prior to Europeans arriving and who was making this claim in the name of historical accuracy.

But Dune.

Dune is told from the point of view of the coloniser. There’s a lot here about the meeting of different cultures – particularly of the Empire and those who live on Arrakis but this is to be blind to much while acknowledging only the most obvious – that those who come to Arrakis to harvest spice are outsiders, who take what isn’t theirs and tell the story that it belongs to them regardless of the fact they’re coming into someone else’s home to take it.

It is the imperial story writ large. What I mean by that is expansionary empires always tell themselves a story that what they’re taking belonged to them anyway or, at the very least, was being wasted by those from whom it’s been taken.

Whether with the velvet glove or the iron fist, the exercise of control is what it is. You can be kind or you can be cruel but if your underlying goal is control then both your kindness and your cruelty are purely performative. Whether you’re Duke Leto Atreides or Baron Harkonnen is irrelevant because you both commit the same Ur-sin: that of deciding what is not yours belongs to you and of erasing those from whom you are taking it. After that first step those people you are robbing are a problem to be solved – either through allyship and bargaining as Leto wished for or with violence and actual erasure which the Harkonnens pursued. You might argue that Stilgar asks to be left alone, that he doesn’t mind the colonisers taking the Spice, but at this point he knows full well he has no chance of making them stop – if they were open to that they wouldn’t be on planet in the first place.

Whether with the velvet glove or the iron fist, the exercise of control is what it is. You can be kind or you can be cruel but if your underlying goal is control then both your kindness and your cruelty are purely performative. Whether you’re Duke Leto Atreides or Baron Harkonnen is irrelevant because you both commit the same Ur-sin: that of deciding what is not yours belongs to you and of erasing those from whom you are taking it. After that first step those people you are robbing are a problem to be solved – either through allyship and bargaining as Leto wished for or with violence and actual erasure which the Harkonnens pursued. You might argue that Stilgar asks to be left alone, that he doesn’t mind the colonisers taking the Spice, but at this point he knows full well he has no chance of making them stop – if they were open to that they wouldn’t be on planet in the first place.

The film tells the empire’s story, not that of the people of Dune. It tells it from their perspective even though those most deeply affected are not the small number of House Atreides and Harkonnen involved but the literal millions of Fremen who live on the planet being plundered.

Villeneuve subverts this but only so far. We’re given real insight into what those Fremen who encounter each of the protagonists feel about them as well as how they respond to the vice like grip the empire has on their lives and culture.

When Jessica shows she knows the Fremen tongue it’s enough to bring rapture to those hearing it because it’s such a rare thing (although that’s not the only reason).

When Stilgar spits, the council’s acceptance of his behaviour is patriarchal, not that of peers. It is accepting, tolerating, not standing on in childlike wonder and learning.

When Stilgar spits, the council’s acceptance of his behaviour is patriarchal, not that of peers. It is accepting, tolerating, not standing on in childlike wonder and learning.

When outsiders arrive they are greeted with cheering crowds because that is the shape those crowds have been squeezed into in order to survive.

The subtlety of Villeneuve’s commentary on the shape the colonised are squeezed into is nuanced and light. I suspect many will miss it because they are so used to those things being invisible to them. They are, in other words, used to seeing the world as the Harkonnens or Atreides see it – as those for whom everything exists. They might even go so far as to say there’s not much politics in the film.

Right at the heart of this discussion sits Dr Yueh – squeezed into betrayal, tortured and discarded because, like all colonised people he is nothing more than a tool to be used and then thrown away when his use expires. Yet Yueh had no choice – how could anyone not act to save those they love if offered the chance, especially if the alternative is to know for sure those loved ones have been murdered because you did not act? Yueh is not a simple traitor. He is the squeezed subject forced to betray himself for hope and that is the tragedy, not his betrayal of Duke Leto. Our sympathy should be with Yueh not Atreides.

Right at the heart of this discussion sits Dr Yueh – squeezed into betrayal, tortured and discarded because, like all colonised people he is nothing more than a tool to be used and then thrown away when his use expires. Yet Yueh had no choice – how could anyone not act to save those they love if offered the chance, especially if the alternative is to know for sure those loved ones have been murdered because you did not act? Yueh is not a simple traitor. He is the squeezed subject forced to betray himself for hope and that is the tragedy, not his betrayal of Duke Leto. Our sympathy should be with Yueh not Atreides.

None of this diminishes the political struggle between the two great houses but it allows us to put it into its true context – the squabbling of factions within a colonial power. Neither Atreides nor Harkonnen can conceive of a world in which the Fremen self-determine.

The best they can manage, which is Duke Leto’s aspiration, is to have the Fremen as a kind of client state.

I’ve read a lot of nonsense about how this is a fantasy telling of Lawrence of Arabia and the Arabian peninsula. That’s to both misread the history of that part of the world and to misunderstand what Lawrence was trying to achieve (and to forget how Lawrence ended his days – disillusioned and heartbroken at his own failures and those of the people he thought he was representing). It’s convenient because of oil and Wahabi Islamism but it’s also wrong in just about every respect.

I’ve read a lot of nonsense about how this is a fantasy telling of Lawrence of Arabia and the Arabian peninsula. That’s to both misread the history of that part of the world and to misunderstand what Lawrence was trying to achieve (and to forget how Lawrence ended his days – disillusioned and heartbroken at his own failures and those of the people he thought he was representing). It’s convenient because of oil and Wahabi Islamism but it’s also wrong in just about every respect.

Lawrence is not Paul Atreides, not even in an idealised version. Bizarrely, Lawrence saw the peninsula more clearly than anything Herbert achieves in his novel while at the same time utterly failing to understand the imperial imperative – which is never to retreat, never to cede territory and never to acknowledge the colonised are fully equal to those who colonised them.

Herbert did, I think, understand this element of the colonial mindset, perhaps a little too enthusiastically but that’s neither here nor there.

Villeneuve interrogates this in several scenes where the subtlety of his film making is wondrous. The planting of the Date Palms and what it takes to keep them alive, the lives sacrificed to give them sustenance is just one moment where the film manages to take something and fill it with ambiguity.

Villeneuve interrogates this in several scenes where the subtlety of his film making is wondrous. The planting of the Date Palms and what it takes to keep them alive, the lives sacrificed to give them sustenance is just one moment where the film manages to take something and fill it with ambiguity.

When Paul asks if they should get rid of such wasteful indulgences he’s met with a response that the trees are sacred.

For whom and why is never answered, leaving us with a sense that perhaps the trees are holy solely unto themselves and that may well be enough for us all.

Villeneuve suffuses the entire film with a sense that everything is unsettled. That times are changing, that something slouches its way to being born.

The story is the story of the coloniser and how they see the world, and the discomfort is perhaps founded on their own acknowledgement that holding onto Arrakis is a project fraught with peril. However, whether it’s Duncan scouting ahead and living ‘like the Fremen’, or whether it’s Paul magically knowing how to wear his Stillsuit without being shown, it rests on the idea that the coloniser can do anything, can win anyone over, can only ever be destined to succeed.

The story is the story of the coloniser and how they see the world, and the discomfort is perhaps founded on their own acknowledgement that holding onto Arrakis is a project fraught with peril. However, whether it’s Duncan scouting ahead and living ‘like the Fremen’, or whether it’s Paul magically knowing how to wear his Stillsuit without being shown, it rests on the idea that the coloniser can do anything, can win anyone over, can only ever be destined to succeed.

It is the hero’s journey as colonial propaganda. For in contrast the Fremen are locked into their world, refusing to leave, refusing to change, refusing to do what they might to be considered the equals of their imperial rulers. It sits in a much broader set of tropes where humans are the jack of all trades while other races are locked into certain racially specific traits. It’s a White supremacist and imperialist trope that goes back centuries and which we continue to see everywhere we look in the genre as well as in wider stories in the mainstream where cultures meet one another – somehow it is always White culture which is flexible, pragmatic and capable.

Paul is shown as being uncomfortable with the role assigned to him and the film questions the idea of the colonisers being superior, but it also shows that from within the view of those same colonisers.

A better analogue is probably French colonialism. Specifically that of Algeria. Arrakis is part of the empire. Algeria was part of France, not simply a colony. Algeria brought down governments and led to vicious and at times fatal infighting among the ruling class of the colonial power with the military caught in between but happy enough to carry out the grim activities required of it.

Arrakis broke those who came to it as much as they fostered dissent among those living there. Indeed in the last scene of the film, Paul wins his right to be called Fremen by killing someone who disagrees with him in ritualised combat. The coloniser once again killing the colonised rather than accepting they do not belong. Killing the distinctive difference, replacing it, transforming it into something they are comfortable with. You could argue that Paul is the most dangerous person in the film – not because of what he becomes later but because of how he unravels the meaning the Fremen put onto the world through their own views of it. This mirrors the French desire to educate and integrate native Algerians into the French way of life and is an extension of his father’s goals for the planet. He stays not because of some sense of destiny but because of Leto’s vision of an army of Fremen allying with Atreides. It is the invader’s dream – that those we’ve conquered might one day willingly serve us as we conquer others.

Arrakis broke those who came to it as much as they fostered dissent among those living there. Indeed in the last scene of the film, Paul wins his right to be called Fremen by killing someone who disagrees with him in ritualised combat. The coloniser once again killing the colonised rather than accepting they do not belong. Killing the distinctive difference, replacing it, transforming it into something they are comfortable with. You could argue that Paul is the most dangerous person in the film – not because of what he becomes later but because of how he unravels the meaning the Fremen put onto the world through their own views of it. This mirrors the French desire to educate and integrate native Algerians into the French way of life and is an extension of his father’s goals for the planet. He stays not because of some sense of destiny but because of Leto’s vision of an army of Fremen allying with Atreides. It is the invader’s dream – that those we’ve conquered might one day willingly serve us as we conquer others.

Parisian elites stayed in Algeria for much the same reason – justifying all kinds of murder and erasure of culture in the name of that goal.

Leto’s arrangement with the Fremen – let us take what we want and we won’t harm you – is just that same colonial idea writ large. Give us the power and wealth we came here for and you’ll be left alone. Which of course was never the case as broken treaty after broken treaty in the Americas and in Africa demonstrate only too well.

It’s worth thinking a little about the iconography of Harkonnen vs. Atreides. The bull, the dress, the artwork combine with an East Asian aesthetic to bring a deliberate sense of calm and thoughtfulness to Atreides. The green exteriors, the rugged cliffs and wild oceans are redolent of civilisation in harmony with nature. We feel they’re more reasonable simply by being in their space. Why? Because these kinds of symbol and design decisions are human sized, relatable and give us a strongly European sense of being – even if some of the sparsity and clean lines are more strongly Japanese (at least to me).

In contrast Harkonnen space feels like capitalism unfettered – brutalist and sterile. We are presented with a House prepared to do anything to increase its supply of capital. If the Atreides are Apple then the Harkonnen are Union Carbide, or worse still, The East India Company. The Baron’s gluttony is deeply symbolic of the rapaciousness of capitalism while Leto’s relative asceticism is more Puritan in bent but no less capitalist. Yet make no mistake, both are beasts of imperial capital. Both are capitalists intent on providing their product to their consumers.

In contrast Harkonnen space feels like capitalism unfettered – brutalist and sterile. We are presented with a House prepared to do anything to increase its supply of capital. If the Atreides are Apple then the Harkonnen are Union Carbide, or worse still, The East India Company. The Baron’s gluttony is deeply symbolic of the rapaciousness of capitalism while Leto’s relative asceticism is more Puritan in bent but no less capitalist. Yet make no mistake, both are beasts of imperial capital. Both are capitalists intent on providing their product to their consumers.

I realise I’ve repeated this argument twice in the last few hundred words but it’s because there’s two things to say about it. The first being that we see the world from their point of view, but the second is another of the subversive elements: the Houses of the Imperium are as trapped in their places as the Fremen. There isn’t really a coloniser who can come and do what the Fremen can’t. Atreides and Harkonnen are just as mired in their ideas and myths and narratives as anyone else. Their paths just as tragically inevitable.

That would be enough all by itself; a story about imperial invaders and the havoc they wreak on those they colonise even when it’s their own internal conflicts driving them.

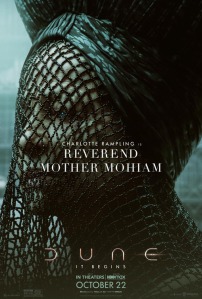

Yet to the side enter the Bene Gesserit. A religious order, perhaps the religious order of this world and they come with their plans for how the world should be.

Yet to the side enter the Bene Gesserit. A religious order, perhaps the religious order of this world and they come with their plans for how the world should be.

As one perceptive character notes, the Bene Gesserit are on no one’s side but their own. Do they have a real world analogue? They are a mix of catholic religious orders and, I’m sad to say, stereotypes about Jewish mysticism. This isn’t Villeneuve’s fault and he does a good job of scrubbing these resemblances away but they remain in the DNA just as calling the supposed saviour the Fremen are waiting for a Mahdi roots us solidly in Islamic North Africa and the Middle East.

I’m not overly concerned – the source material makes these allusions part of its very structure. What’s more interesting is the role religion plays in the story and world we see in this incarnation.

The colonialists side eye the Bene Gesserit, not quite willing to disregard them entirely but also not observant themselves. Even Leto isn’t a believer despite taking one as a lover and mother of his only son. In the end colonists and empires relate to religion as they do to everything – how can it help me achieve my goals?

Leto complains that after a religious encounter, Paul is distracted, not focused on their mission – which is the colonial extraction of wealth from the subjugated territory. That right there is a deep insight into the colonial mindset – believe what you will as long as it doesn’t interfere with what we want.

Leto complains that after a religious encounter, Paul is distracted, not focused on their mission – which is the colonial extraction of wealth from the subjugated territory. That right there is a deep insight into the colonial mindset – believe what you will as long as it doesn’t interfere with what we want.

The film is not Christianity vs. Islam with Judaism scheming in the background although a surface read could see it that way. The religions of Dune’s world are similar in structure just like the three religions of the Book but they are also just as different.

I loved the idea that the Bene Gesserit were proselytising among the Fremen, not to convert them but to inculcate them into prophetic ideas, to co-opt the Fremen’s own eschatology and turn it against both themselves but also against the Empire. Why? Because they believe the world should be a certain way and those who disagree should be changed to come into line. They are, as much as Leto or Harkonnen, colonisers.

Perhaps more interestingly they’re a direct competitor to the colonial ambitions of the Houses and the Empire. It is why they’re distrusted, because they offer an alternative colonial narrative.

Rebecca Ferguson delivers an incredible performance as Jessica, the priest whose faith and motherhood rest on the son she’s literally engineered into the world. She has coloniser’s hopes for him – that he will rule, that he will ascend and change the world. When she thinks of a better world she doesn’t think of Fremen independence – she is thinking of a world like the one she lives in with Leto, one where the Harkonnen are a memory. It aligns with Leto only in that he wants the world he’s built to be the dominant one too.

Rebecca Ferguson delivers an incredible performance as Jessica, the priest whose faith and motherhood rest on the son she’s literally engineered into the world. She has coloniser’s hopes for him – that he will rule, that he will ascend and change the world. When she thinks of a better world she doesn’t think of Fremen independence – she is thinking of a world like the one she lives in with Leto, one where the Harkonnen are a memory. It aligns with Leto only in that he wants the world he’s built to be the dominant one too.

The story ends with Jessica and Paul in Fremen lands, having murdered one of the Fremen and demonstrating their evident physical and metaphysical superiority with a view to heading into the depths of the desert for their inevitable personal transformation which will somehow also transform the Fremen into willing subjects in delivering their goals of revenge and conquest.

The last thing I want to talk about is the asymmetry between them and the Fremen. The Fremen are colonised even if fiercely resistant to that colonisation. One can see the pressure on them to be more extreme because that is, frequently, the only real way to resist those who demand you abandon what previously might have only been loose ideas about who you were.

The Fremen do something Paul and Jessica can’t do – they accept them as peers. The Bene Gesserit and Paul remain themselves and continue to regard the Fremen as a subject people giving them aid even while the Fremen pronounce them ‘one of us’. The asymmetry in how the colonised view themselves couldn’t be more apparent here. The colonised can see the coloniser as a peer but the reverse can never be true.

We don’t get the colonised Fremen’s point of view in this film. Nothing we receive is unmediated by the eyes and thoughts and impulses of the colonisers – whoever they might be. Villeneuve’s genius is to make that asymmetry central to the story in a way Herbert didn’t. Villeneuve questions it from a post-colonial mindset, one that can understand other voices might wish to speak and tell their stories. It’s deeply subversive and miles away from Herbert’s questioning of Empire which really focused more on its failures to live up to its promise because of human frailty than questioning it as a venture in the first place.

We don’t get the colonised Fremen’s point of view in this film. Nothing we receive is unmediated by the eyes and thoughts and impulses of the colonisers – whoever they might be. Villeneuve’s genius is to make that asymmetry central to the story in a way Herbert didn’t. Villeneuve questions it from a post-colonial mindset, one that can understand other voices might wish to speak and tell their stories. It’s deeply subversive and miles away from Herbert’s questioning of Empire which really focused more on its failures to live up to its promise because of human frailty than questioning it as a venture in the first place.

Each and every element of Dune, from the music to the trees to the costumes is about empire and the impact of colonisation. It tells this story through the eyes of the powerful not the weak. Nevertheless, it deliberately finds space to entirely undermine the stories those powerful people tell themselves about why they’re doing what they’re doing.

If we care about the post-colony then Dune as adapted and filmed by Denis Villeneuve is a film to watch and understand carefully, for it unwraps the program of colony and empire, places it clearly on the screen and shows us why it is rotten to the core.