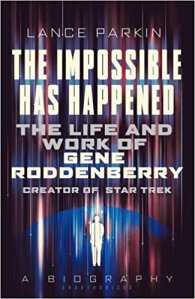

By Lance Parkin

By Lance Parkin

Aurum Press, out now

In which the life, career and creative works of Eugene Wesley Roddenberry are examined – strengths and weaknesses, warts and all – twenty-five years after his passing.

Within televised science fiction, few figures have been as polarising as Gene Roddenberry. Star Trek went from disposable weekly entertainment to pop culture phenomenon, and through carefully orchestrated branding and interactions with fandom, he become a messianic figure with a devoted, almost cult-like following. But after his death in 1991, a variety of anecdotes, tell-all biographies and other books revealed a complicated, deeply flawed man behind the genial façade.

Rather than boldly rehashing what other writers have written before, Lance Parkin offers a broader perspective on Roddenberry and his works, often going pages without mentioning the man as he explores TV network and film studio policies and politics over several decades. Ultimately one cannot help but agree with Parkin about how Star Trek generally succeeded despite its creator rather than because of him (remember “The Omega Glory” and the ponderous pomposity of The Next Generation’s first season?). And Parkin successfully articulates what I had long suspected but never really put into words: “something in his work seems to bring out a certain stiffness in [his leading men], and they tend to end up as a weak point where the solid core of the show should be.” Just look at Jeffrey Hunter in “The Cage”, and be thankful that William Shatner worked against this and made James T. Kirk such a memorable character!

Parkin also examines Roddenberry’s non-Trek works – the little-seen Marines drama The Lieutenant, which guest-starred many future Star Trek regulars; his failed 1970s sci-fi pilots Genesis II (“not very good”), Planet Earth (“endearingly awful, rather than impressive”) and The Questor Tapes (originally intended as a vehicle for Leonard Nimoy), noting how Roddenberry stuck with a limited number of tropes and ruminated on them like a contented cow.

Paramount brought Roddenberry onto the ultimately-aborted Star Trek: Phase II which morphed into Star Trek: The Motion Picture after the runaway success of Star Wars. As the Trek movie he was most involved in, The Motion Picture receives the most coverage, and it’s a morbidly fascinating glimpse into a near-train-wreck of a production with an ever-escalating budget which began filming with an unfinished script. Thankfully it became a box office blockbuster, but the studio chose Roddenberry as its scapegoat and sidelined him from the next five movies as much as possible.

Ultimately, Parkin concludes that while Roddenberry came up with a few great ideas for televisions, he frequently self-sabotaged them through his insistence at being the alpha male; inability to relinquish control; refusal to play studio politics; and frustrating tendency to think of an “interesting… subtle and delicate” idea and turn it into a pompous, ham-fisted finished product. As much as he wanted to be Mr. Spock or the messianic Great Bird of the Galaxy that he and fandom had concocted, he was in fact the most human of humans.

Verdict: A well-written, often page-turning account of the man behind the myth which gives a balanced overview Roddenberry’s strengths and deficiencies, as well as insights into the ways TV and movie studios operated in the 1960s through the 1980s. 8/10

John S. Hall