In part 1 of this interview, Brian Sibley talked about the structure of his adaptation. In this second part, Sibley and director/producer Gemma Jenkins discuss the project’s long road to the airwaves…

In part 1 of this interview, Brian Sibley talked about the structure of his adaptation. In this second part, Sibley and director/producer Gemma Jenkins discuss the project’s long road to the airwaves…

a

a

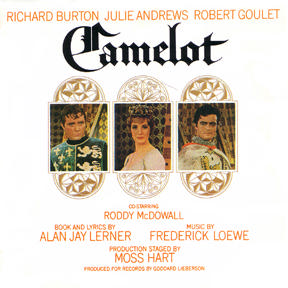

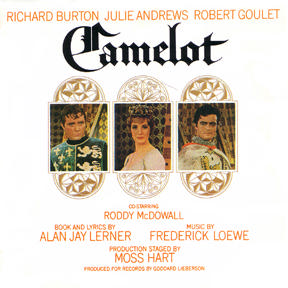

Brian Sibley: Gemma and I have been dreaming of making this series for nearly two years: it was a great opportunity to do something with a book that I really passionately loved. However, the journey was quite nightmarish: I went to Disney first of all because I have contacts there. They put me in touch with their rights department, who thought they owned the rights to the whole book, but it turned out they didn’t. They thought Warner Bros. owned the rights to everything other than The Sword in the Stone. However, Warner Bros. didn’t, and we just followed this course, which led us eventually to American attorneys at law, who were representatives of Alan J. Lerner and Frederick Loewe.

Gemma Jenkins: Both the Disney and the Lerner/Loewe estates have been incredibly helpful and supportive of the process. There was never any real resistance to it as a project, it was more about getting the right people talking to each other. A lot of that was down to our rights exec, Sue Dickson, who was the lynchpin, getting in touch with everyone and getting them talking together. Once we were talking to the right people, it actually happened quite quickly, but it took us about 18 months. Very sadly, the head of one estate died during the process, so we had to allow them time both to grieve and get somebody new in place, but the nice thing was that they were still honouring the point that we’d already reached.

Gemma Jenkins: Both the Disney and the Lerner/Loewe estates have been incredibly helpful and supportive of the process. There was never any real resistance to it as a project, it was more about getting the right people talking to each other. A lot of that was down to our rights exec, Sue Dickson, who was the lynchpin, getting in touch with everyone and getting them talking together. Once we were talking to the right people, it actually happened quite quickly, but it took us about 18 months. Very sadly, the head of one estate died during the process, so we had to allow them time both to grieve and get somebody new in place, but the nice thing was that they were still honouring the point that we’d already reached.

We officially got the go ahead from Radio 4 in July 2013, subject to the rights, and because there are always big series in the pipeline, including at the moment a lot of First World War centenary drama, you have to reserve your space for the studio. This is essentially 12 days on the trot so we had to put that in place early.

At that point, had you actually started scripting?

Brian: No.

Gemma: The structure is all part of the pitching process; you have to do a hell of a lot of work, and wait another year before knowing if it is definitely going to happen.

Brian: When you get the go-ahead, you look at the pitch and wonder why you were going to do it that way. There have been various changes along the way because when you pitch something, it’s not the same as actually writing it – it’s what you think you’re going to write.

Brian: When you get the go-ahead, you look at the pitch and wonder why you were going to do it that way. There have been various changes along the way because when you pitch something, it’s not the same as actually writing it – it’s what you think you’re going to write.

Gemma: It was useful that from the moment it went into production, it was a collaborative process, and [fellow directors] Marc Beeby and David Hunter have been fantastic. You could have one person doing it, but having the input of three people just makes sure you are constantly on the top of your game. In something like the scene we’ve just done, where Elaine is stepping out of the cauldron of water, there are so many different things you’re listening to during the recording; so it’s very useful to have just one person listening who can notice a line that’s a turning point or a lynchpin for a particular scene, and suggest that if you hit it like this… What’s really nice is that you can see the whole process come together: you’re in the firing line for so many days but if you’re there throughout, you can see how individual characters develop, so you know when you come in where they are.

Let’s talk about the casting… Who’s joining David Warner’s Merlyn?

Gemma: Paul Ready is playing Arthur; he was one of the actors in Utopia. Kate Fleetwood is Morgause, the mother of the rebellious Orkney faction; Lyndsey Marshal is Guenever. With radio you’re not always thinking whether the actor looks the part, but what’s really nice is that White makes the point that Guenever is not blond and blue-eyed – in his version she’s dark-haired – so Lyndsey fits that description.

Gemma: Paul Ready is playing Arthur; he was one of the actors in Utopia. Kate Fleetwood is Morgause, the mother of the rebellious Orkney faction; Lyndsey Marshal is Guenever. With radio you’re not always thinking whether the actor looks the part, but what’s really nice is that White makes the point that Guenever is not blond and blue-eyed – in his version she’s dark-haired – so Lyndsey fits that description.

Alex Waldman is Lancelot; he recently done a couple of big radio dramas, and is highly thought of. Sam Dale, who’s a radio drama stalwart, is playing King Pellinore and Uncle Dap; it’s great to have actors who can do that. We’re able to double up in the way other mediums can’t – on radio you wouldn’t know it was the same actor. Mordred is Joel MacCormack, who won BBC Radio’s Carleton Hobbs competition in 2013. And Edward Bracey is playing Wart; he’s 14, and fantastic. He pretty much carries the first two episodes with Merlyn.

Brian: I’ve always admired David Warner for so many reasons. He’s probably one of the most underrated great actors of his generation and I don’t know why that should be. He has an extraordinary body of stage work – he’s the Hamlet of his generation without question – and an amazing filmography with so many cult films among them: he was in Morgan – A Suitable Case for Treatment, Tron, Time Bandits, The Omen and so many others.

He has an ability to play a massive range of emotions, intensity and colour, and is an intuitively intelligent actor who knows how to read a line and bring so much to it. I’ve had the privilege of working with him three times: the first time I dramatized the Mervyn Peake stories, he played Lord Sepulchrave, the head of the family, ‘the melancholy lord of half-light’, as Peake describes him, and was hugely moving in that. Then when I did The History of Titus Groan [to be repeated on BBC Radio 4 Extra at the start of 2015], he came back and played the Artist – a narrator character who was essentially Mervyn Peake.

He has an ability to play a massive range of emotions, intensity and colour, and is an intuitively intelligent actor who knows how to read a line and bring so much to it. I’ve had the privilege of working with him three times: the first time I dramatized the Mervyn Peake stories, he played Lord Sepulchrave, the head of the family, ‘the melancholy lord of half-light’, as Peake describes him, and was hugely moving in that. Then when I did The History of Titus Groan [to be repeated on BBC Radio 4 Extra at the start of 2015], he came back and played the Artist – a narrator character who was essentially Mervyn Peake.

I’m thrilled he’s in this: he’s been a very lucky mascot for me. The first of those productions won two Sony Radio Awards, the second one won the BBC Drama Award. He brings so much to this – his relationship with Paul Ready is excellent.

One of the best things that any writer can hope for – unless you’ve got such a massive ego that you want everybody to know you’ve written a particular line – is to hear an actor say lines as if they’re being said for the first time having just been thought, rather than being written down on a page. Both Paul and David have that ability.

We’ve talked about the structure of the series, but how else is this different from a normal radio drama?

We’ve talked about the structure of the series, but how else is this different from a normal radio drama?

Brian: In something like The Barchester Chronicles, pretty much all the characters are set up at the beginning and then you follow them through however many episodes. The joy of The Once and Future King is that, because it spans the childhood to full maturity of King Arthur, every episode brings in new characters. We encounter King Pellinore in episode 2, Queen Morgause in episode 3, Uncle Dap in episode 4… Each episode has Arthur and Merlyn, but there are guest characters. It’s a really nice quality that keeps the story fresh for listeners.

It’s probably also fair to say that we’ve used quite a few radio techniques: there is very straightforward drama – even if it’s dealing with unreal circumstances – but then for one of the big battles, we don’t have hundreds of people rushing round clanking armour and bashing with swords (whilst that might work visually on film, it tends not to work terribly well as just a melee of sounds); so, instead, we have the battle remembered and recounted by Arthur and Merlyn in the present tense, augmented with a stylized version of battle sounds. There are other points, such as the Badger’s story of the creation of the world, where we go into something which is pure story-telling. That’s a Jackanory moment of “just sit down and we’re going to tell you this story”. There are lots of moods and styles within the series, which I hope people will cope with.

Were you tempted to update White’s anachronisms?

Brian: We talked about updating the references and my original thought was to do so, but in the end I decided not to, with one or two small-ish diversions. For the most part I’ve stuck fairly closely to White’s own anachronisms. When I wrote the scene of Wart arriving in Merlyn’s cottage, he was going to make passing reference to books about magic and witchcraft, and mention “everything from Doctor Dee to Harry Potter – all largely fanciful”. But then I thought anything that steps out of TH White’s lifetime is too risky – with two exceptions. When he’s telling Arthur about all the versions of the legend that will appear, I was determined that White’s self-referential quote would be there (“and then there was old White of course – what an anachronist he was”), and I have included Disney and Lerner & Loewe in the list of future interpreters. White was aware of all those things happening – The Sword in the Stone was made in his lifetime, and while I don’t think he ever met Walt Disney, he certainly met and got to know Alan J. Lerner. He went to New York, and was present at all the last rehearsals of Camelot. He also became a very close friend of Julie Andrews and Tony Walton who bought a house on Alderney to be near him.

Brian: We talked about updating the references and my original thought was to do so, but in the end I decided not to, with one or two small-ish diversions. For the most part I’ve stuck fairly closely to White’s own anachronisms. When I wrote the scene of Wart arriving in Merlyn’s cottage, he was going to make passing reference to books about magic and witchcraft, and mention “everything from Doctor Dee to Harry Potter – all largely fanciful”. But then I thought anything that steps out of TH White’s lifetime is too risky – with two exceptions. When he’s telling Arthur about all the versions of the legend that will appear, I was determined that White’s self-referential quote would be there (“and then there was old White of course – what an anachronist he was”), and I have included Disney and Lerner & Loewe in the list of future interpreters. White was aware of all those things happening – The Sword in the Stone was made in his lifetime, and while I don’t think he ever met Walt Disney, he certainly met and got to know Alan J. Lerner. He went to New York, and was present at all the last rehearsals of Camelot. He also became a very close friend of Julie Andrews and Tony Walton who bought a house on Alderney to be near him.

And inevitably you’ve had to make some cuts.

Brian: Because it’s such a big book and there’s so much in it, there will undoubtedly be some person’s favourite stuff which has not made its way in there – some of my personal favourites haven’t – but we only have six hours. More than anything I hope it will send people back to read the books again.