Interview: Chuck Wendig

Chuck Wendig’s latest novel The Book of Accidents has just been published either side of the Atlantic, a horror tale that draws the reader into its story of haunting and […]

Chuck Wendig’s latest novel The Book of Accidents has just been published either side of the Atlantic, a horror tale that draws the reader into its story of haunting and […]

Chuck Wendig’s latest novel The Book of Accidents has just been published either side of the Atlantic, a horror tale that draws the reader into its story of haunting and terror. With Wayward, a sequel to his SF tale Wanderers, coming next year, and a new middle-grade book Dust & Grim out in the autumn, it seemed to Paul Simpson to be a good time to catch up with the Pennsylvania-based author…

Chuck Wendig’s latest novel The Book of Accidents has just been published either side of the Atlantic, a horror tale that draws the reader into its story of haunting and terror. With Wayward, a sequel to his SF tale Wanderers, coming next year, and a new middle-grade book Dust & Grim out in the autumn, it seemed to Paul Simpson to be a good time to catch up with the Pennsylvania-based author…

The books that you’ve written in recent years, whether it’s the Star Wars trilogy or Wanderers or The Book of Accidents are much bigger novels than your earlier ones. Are you having to do a lot more plotting before you sit down in front of the computer or are you going ‘I know what the story is, let me get it out there’?

I had generally done quite a lot of plotting; plotting was the thing I felt like I had to do because if I didn’t, I always felt like I was kind of lost in the story, like I was wandering around like it’s a maze.

But with Wanderers and The Book of Accidents I actually didn’t do much plotting. Especially with The Book of Accidents, that was a “let’s just jump out of a plane and build the parachute on the way down”. It was definitely both a trust exercise and a moment of chaos and joy to some degree, because it’s fun to do that with that book.

You’ve said that it was a book that you’ve had around in your head for a long time and Robert McCammon told me a few years back about books that he knew he wasn’t able to write when he had the idea but reached the stage where he could later. Was it a similar sort of thing for you with this?

You’ve said that it was a book that you’ve had around in your head for a long time and Robert McCammon told me a few years back about books that he knew he wasn’t able to write when he had the idea but reached the stage where he could later. Was it a similar sort of thing for you with this?

Yes, it’s one of those things where sometimes books are the wrong book and sometimes they’re the right book but you’re the wrong writer for them and it’s tricky to get to that realisation! This is just one of those books where I just wasn’t ready.

In what way?

It’s a big gnarly book that needs the ability to look back and it needs time. Recently I moved back to the area in which I grew up. I’m also a father, and my father has since passed away, so there’s been a lot of confluence of events that contextualise the book and had it make more sense to me.

Was there an image or a memory that actually kickstarted the book for you in the first place?

It’s a lot of things: growing up in a complicated family but also growing up in a haunted house (laughs) – those two things add up to the desire to tell a story like this. And also to reach beyond the haunted house and find something deeper and squirrely-er in the horror vein as to what a haunting actually means and what that can metaphorically or figuratively translate to in the narrative.

What was haunted about your house?

What was haunted about your house?

We had all kinds of things happen over the course of my entire time there. A lot of electronic stuff: TVs would come on in the middle of the night, the boombox next to my bed would turn on and start playing at top volume, or a VCR would kick out a tape or ruin a tape or began to fast forward or rewind. You’d hear footsteps. Sometimes there’d be the feeling of another presence or something standing in the doorway. Sometimes there was weird singing outside, which you could hear in the walls.

It was a strange house to grow up in, it was a very old house – not by your standards, old by our standards!

Civil War era?

No pre. In our area we always joked that George Washington slept here which is what they always said about every house in that area! And it’s surely a lie, he could not have slept in every house in this area, but it was only ten miles away to where he crossed the Delaware. We’re steeped in that Revolutionary/pre-Revolutionary history.

Given you’ve grown up with that, does that give you more of an interest in it? For some people it would make them want to debunk ghosts or the supernatural more.

I grew up with it and even I still feel sceptical about it. I know what I experienced and I know how the pieces line up. I was not the only person to experience things; other people experienced them with me or separately from me. So I always felt like it was happening, whether I was hearing sound waves, or whatever the explanation du jour is. I’m comfortable with it being something I don’t quite understand.

Even still I don’t know if it is what it is, or if it’s something different, but it definitely was real in that sense that we were experiencing things. So it felt pretty real.

One of the things I noticed looking back over your writing, going right back to the Miriam Black novels and Mookie, there seems to be a certain fascination with liminal places. Is that something that I’m seeing that isn’t there?

One of the things I noticed looking back over your writing, going right back to the Miriam Black novels and Mookie, there seems to be a certain fascination with liminal places. Is that something that I’m seeing that isn’t there?

It’s there. I don’t know why, this aspect of liminal interstitial places, places that are between what we know. The simplest explanation for it is that those are maybe the most interesting places, but actually when you’re dealing with anything related to horror, horror and the supernatural thrive on the unknown so the things that we don’t know are often those things that fall between the cracks that don’t make sense.

Even death: we can’t know it until it’s done and I don’t know what happens after that, but it still feels like the stuff that’s between those two things, or that is outside of those things, is the true unknown. It feels particularly alien and unusual and that’s usually the places to explore narratively but also to freak people out.

It’s like the dark. The darkness is scary because you can’t see things. At the very simplest level, the less light you have the freakier it feels, simply because you’re like ‘I don’t know, someone could be reaching out in this dark space and they could have their hand inches from my face and I would not know’ and that feels terrifying.

Ghosts represent that same kind of thing: are they dead? Or are they demons messing with us? Or are they soundwaves or magnetic fields that are goofing with our head? Either way, the simple fact is we don’t know and there’s no scientific evidence for it and no supernatural evidence. You can’t have evidence for ghosts. We’d be a revolutionarily changed society if we were like ‘Here’s confirmed proof of the dead or the spirits or the supernatural’, whatever it was.

It’s that unknown, that question mark that you feel certain that something was there, you feel certain that there was an experience, but the practicality of it, the reality of it exists in this unknown, as you say, liminal space. I think that’s definitely an interesting playground.

And of course the flip side of that is faith is a total trust that something is in charge of that.

And of course the flip side of that is faith is a total trust that something is in charge of that.

Yes and the lack of faith that there is, that can be scary too. Wanderers is a book that deals a lot with faith. As much as it’s a big sprawling sci-fi horror epic, a lot of what it’s dealing with, including the sequel which I just finished writing the first draft of, is faith and questions of what people believe in, where they place that heart of theirs in that understanding.

Do you find when you’re writing something like that that it actually changes your own personal feelings about areas because you’ve had be almost a devil’s advocate for the other side of the argument?

Yes, I think there’s definitely that, because empathy is essential to tell a good story. Not sympathy necessarily, you’re not there to feel that level of ‘Oh no, boo hoo’ for a character, but I think even the worst possible characters there’s something in trying to figure out where they come from.

I have no doubt that in real life there are people whose evil is in some way simply pure, that it’s unfounded and they are who they are, but at the same time you try to examine why people do bad things and there’s usually something there. Not to say it’s justified, only that there’s a seed that grew into that nasty tree.

I think that’s the most interesting thing about all that and playing with that, I do change my own mind sometimes. Not in a sense that I feel like I have some revelation but challenging the ideas of how science and faith work together and not necessarily apart was something that I thought was interesting to explore and it certainly tweaked my understanding of that.

The Book of Accidents starts as a haunted house story and a tale of a boy trying to deal with what’s going on around him in a new environment and it becomes something much bigger. Did you always envisage that it was going to take on that extra dimension?

Yes, I always knew that it was something more than it was. I’m a very greedy storyteller. Wanderers was the same way. I’m not content to write five books covering these five different things. I am fascinated with the idea of how you can put a lot of strange, sometimes opposite pieces interlocking and how you fit these things together. Just on a reader level, it’s great to let people expect one thing and then continually stick that knife in and continue to twist it and see what loops and pulls out of them. So for me starting with a haunted house and moving beyond the walls of that house into a haunted world and seeing where I could take that was fun.

Yes, I always knew that it was something more than it was. I’m a very greedy storyteller. Wanderers was the same way. I’m not content to write five books covering these five different things. I am fascinated with the idea of how you can put a lot of strange, sometimes opposite pieces interlocking and how you fit these things together. Just on a reader level, it’s great to let people expect one thing and then continually stick that knife in and continue to twist it and see what loops and pulls out of them. So for me starting with a haunted house and moving beyond the walls of that house into a haunted world and seeing where I could take that was fun.

I didn’t know precisely what that meant when I was writing it. I just knew it wasn’t kept to one thing.

Was the numerology element to it there from the start?

The numerology element which comes in the serial killer [plotline] is false to some degree. Without getting too deep into spoilers, people are fed information and they believe they are given purpose. This madman, this serial killer, believes these equations and numbers add up to something meaningful for him, but he’s been told this story. It’s mostly a lie: there is still a numerological component to the number 99 but how it all adds up is mostly just a way to convince him to bring more pain into the world. It’s like mythology, folklore, that can be false for the most part whilst having a true underpinning maybe at the very core of it.

It’s that idea of ritualised occult folklore type stuff that is a shellacking over maybe a deeper truth about pain and abuse and suffering that can be caused and delivered to other people.

The nastier characters in this feel a lot nastier than those in the Miriam Black series…

Yes, there’s something about the Miriam books. While I still do consider them horror crime novels, they’re also much pulpier, so it’s a little more cinematic. There’s still evil and grotesquery going on there but it’s a little more overtly fictional, whereas a lot of The Book of Accidents, obviously while still very fictional, I tried to cleave to a little bit of reality in terms of how some of the people act or think.

Yes, there’s something about the Miriam books. While I still do consider them horror crime novels, they’re also much pulpier, so it’s a little more cinematic. There’s still evil and grotesquery going on there but it’s a little more overtly fictional, whereas a lot of The Book of Accidents, obviously while still very fictional, I tried to cleave to a little bit of reality in terms of how some of the people act or think.

Some of what’s in the book is based on a murder that happened not even a quarter of a mile from my house when I was probably about a year old. [The murder of Shaun Ritterson] is one that I understood later upset my parents considerably, understandably. My father started keeping loaded guns around the house just because of what happened.

A girl was disembowelled on the side of the road and left, and she was stuffed with a towel. It was brutal and it’s never been solved even now. Just this week there was news about the case, that they returned the victim’s ring to the family. The ring was one of the linchpins in trying to identify her, because for a long time they didn’t know who she was and her ring said ‘love’ on it. They settled on it was most likely it was her uncle who did it, but he’s passed and the evidence had degraded enough that they can’t quite get to the point of pointing the finger at him.

But people believed it was a cult and satanic because of the way she had been left and possibly disembowelled while she was alive. People still remember that and they still talk about that. They don’t talk about it in an overt way; it’s usually when people start drinking they talk about it, or when it’s late night they start, ‘Hey, how about that cold case?’ I think it’s interesting how that left a mark on the area in both the motivation for the killing and what it did to that whole spot in our township and history of the area.

But people believed it was a cult and satanic because of the way she had been left and possibly disembowelled while she was alive. People still remember that and they still talk about that. They don’t talk about it in an overt way; it’s usually when people start drinking they talk about it, or when it’s late night they start, ‘Hey, how about that cold case?’ I think it’s interesting how that left a mark on the area in both the motivation for the killing and what it did to that whole spot in our township and history of the area.

It’s that unanswerable thing again, that thing that doesn’t quite have a solution, no neat and tidy answer to it that’s more upsetting. It’s why someone like Edward Walker Reese in the book is so desperate for what he believes are answers because it makes him feel justified in what he does.

On a technical point, most of your earlier stories were written in present tense, but with Wanderers and this you’ve moved to past. You’ve also moved to longer paragraphing. Is that conscious because that’s what the stories needed or is it just the way that your own storytelling is evolving?

It’s conscious. In fact both Wanderers and I think The Book of Accidents delve a little bit into present tense for maybe a section or two, but generally they are past tense novels because present tense is very good in a small book, I find.

It’s conscious. In fact both Wanderers and I think The Book of Accidents delve a little bit into present tense for maybe a section or two, but generally they are past tense novels because present tense is very good in a small book, I find.

[The Star Wars trilogy] Aftermath probably pushed the boundaries of that, which I know some people did like and some people didn’t, but when you’re writing something that I want to feel cinematic and thrillery – not that every book of mine isn’t to some degree – I want you to feel edge of your seat, like you’re falling forward into it. The Miriam books are like a bullet out of a gun and you’re just chasing after it – I want you to feel like you’re watching someone paint a painting rather than looking at a painting.

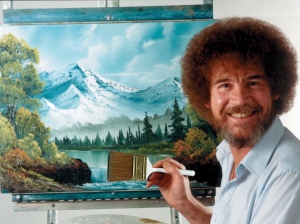

I think with Wanderers and The Book of Accidents I want you to look at the painting that’s been completed and find the things in it, let your eyes roam over it continually and maybe reread, it but with Miriam, I want you to feel like you’re simply unsure as to what is going to be painted next.

We have an old show over here featuring Bob Ross the painter. It was always funny because you’d be watching him paint and for twenty of the thirty minutes you’d be, ‘I don’t know what he’s painting, this does not look good’ and then you’d say ‘ Finally, I got ya! You’re going to paint a bad painting this time and it’s not going to look good’. And then somewhere right at the end he would pull it out – it was a plane nosedive pull. But that’s just the nature of painting because so much of those sublayers are not meant to look like anything – they’re just shapes and contours – then suddenly you bring out the detail and the thing emerges.

We have an old show over here featuring Bob Ross the painter. It was always funny because you’d be watching him paint and for twenty of the thirty minutes you’d be, ‘I don’t know what he’s painting, this does not look good’ and then you’d say ‘ Finally, I got ya! You’re going to paint a bad painting this time and it’s not going to look good’. And then somewhere right at the end he would pull it out – it was a plane nosedive pull. But that’s just the nature of painting because so much of those sublayers are not meant to look like anything – they’re just shapes and contours – then suddenly you bring out the detail and the thing emerges.

That’s what present tense always brought to the table for me: this idea of ‘I can’t quite see where this is going yet because I’m not looking at a finished painting’. There’s nothing to hold onto, it’s just you moving forward with me, and hopefully they feel chaotic and unpredictable. With something like Wanderers and The Book of Accidents I want you to be in a thing that feels completed already in that it feels inevitable in a sense.

One of the things I commented on when we spoke last time was that I always felt, particularly with the Miriam books, that I was experiencing the emotions with the characters and I think part of that comes out of the present tense. You achieve the same thing with point of view, and language changes in the POV. Is that difference something that comes out as you’re writing or is that something that you need to hone in the edit?

It’s always honed in the edit but it is something I try to bring out clearly and forthright in the first draft, just so I know what I’m holding onto when the edit comes. If you start to do that in the first draft then by the time you’re doing your second or third and whatever drafts you’re going to do, you’re more bringing it out than having to revise it or add it. It’s like you’re trying to bring the image further out of the rock. The first crude carving you want to highlight the details, you know where the eyes are supposed to go, now it’s time to really refine those points.

It’s always honed in the edit but it is something I try to bring out clearly and forthright in the first draft, just so I know what I’m holding onto when the edit comes. If you start to do that in the first draft then by the time you’re doing your second or third and whatever drafts you’re going to do, you’re more bringing it out than having to revise it or add it. It’s like you’re trying to bring the image further out of the rock. The first crude carving you want to highlight the details, you know where the eyes are supposed to go, now it’s time to really refine those points.

The image quality of a VHS recording going to 4K, it’s that…

Exactly yes! It’s like click enhance in a movie.

What did you find was the biggest challenge in writing The Book of Accidents?

The edit. It was a big edit. It’s great when an edit is like ‘oh these chapters don’t work, cut them’ because then you’re like ‘OK, I can cut them and stitch the resulting flesh together’. When I talked to my editor about this, it was like rewiring sinew and capillaries. The book was the book, and what was there was there, and it needed to be more of that. So you’re trying to move little pieces here and there and breaking apart a chapter so it feels a little more urgent. It was just this different kind of unruly gnarly edit and essential.

My editor Tricia Narwani is wonderful and it was so vital to do that. It was really an important lesson in learning how to do an edit like this. I don’t know that I’ve ever done an edit that was quite this squirrely but I think it was for the best to take the time.

I did that during the pandemic. I wrote the book a good bit before the pandemic and it was actually supposed to be out in October of 2020 but then we decided to move it due to the election! We were not going to be able to get any traction on media but it did give more time, which was an advantage to pick through the pieces and keep moving those capillaries around and see how the blood flowed best. A good editor is gold, absolute gold.

I did that during the pandemic. I wrote the book a good bit before the pandemic and it was actually supposed to be out in October of 2020 but then we decided to move it due to the election! We were not going to be able to get any traction on media but it did give more time, which was an advantage to pick through the pieces and keep moving those capillaries around and see how the blood flowed best. A good editor is gold, absolute gold.

So what’s next?

Wayward will be out next year and this October I have my first middle grade coming out called Dust & Grim, about a girl who inherits a funeral home for monsters and she has to share the inheritance with her brother who she’s never met. That just got a starred review on Kirkus today so it’s a good morning.