Interior Chinatown: Review: Series 1

A Chinese waiter witnesses an abduction… I did not see this show being talked about anywhere (Disney+ on which it streams has had no elevation of it in its algorithm […]

A Chinese waiter witnesses an abduction… I did not see this show being talked about anywhere (Disney+ on which it streams has had no elevation of it in its algorithm […]

A Chinese waiter witnesses an abduction…

A Chinese waiter witnesses an abduction…

I did not see this show being talked about anywhere (Disney+ on which it streams has had no elevation of it in its algorithm as far as I can tell). I only found it because it was recommended to me by an old publishing friend.

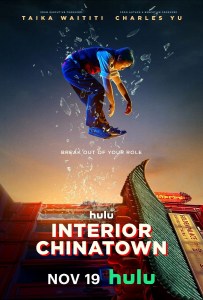

By the end of the first episode I was hooked – and not just because of the story which has a lovely beauty all of its own. Based on the novel by Charles Yu with a fairly large writing and directing team including Taika Waititi, the show stars, among others, Chloe Bennet, Jimmy O. Yang and Ronny Chieng, all of whom get to do interesting things with great material in a masterfully told narrative.

Like, seriously, this is some of the tightest plotting and character development I’ve seen in genre and elsewhere. It’s up there with the greats.

What’s keeping it from superstardom? The same thing, that for me, makes it incredible to watch. It’s a genre show about stories, our cultures, how decisions get made about who gets to do what, how we navigate our lives for meaning and how, in the end, we might come back to ideas that the modern world too often tells us are worthless or secondary.

It’s worth talking about the central story because it informs everything else. Often with a series you can review the themes, the metaphors, the subtext and there’s barely any need to cover what actually happens. Interior Chinatown’s story is crucial to its meaning.

Willis Wu is a waiter at a Chinese restaurant in Port Harbour’s China Town district. His best friend smokes weed, gets drunk, hates his job at the family restaurant and loves playing the Double Dragon clone arcade machine in the staff area by the kitchens.

Willis Wu is a waiter at a Chinese restaurant in Port Harbour’s China Town district. His best friend smokes weed, gets drunk, hates his job at the family restaurant and loves playing the Double Dragon clone arcade machine in the staff area by the kitchens.

When a young nail salon worker is kidnapped and Willis witnesses the abduction he is determined to help find her and uncover what’s going on in his neighbourhood.

Except the world appears to have other ideas. When he tries to rush out to tell the police he’s a witness he discovers the doors to the restaurant won’t open. When he goes to the police station to tell them what he saw he discovers that no matter how hard he tries he can’t get in.

When I say the world is trying to stop him, I mean the world itself – this is metaphor wrapped up in concrete actualisation, the idea made flesh.

Willis is not the only person to have discovered that the world appears to change around him when he does something that doesn’t fit with the script of being a background waiter. His brother, who disappeared a decade ago, seemed to have found that when he pushed against these invisible boundaries they pushed back. So he sets out to discover not only what happened but also how it’s linked to his brother’s disappearance.

The show tackles all kinds of questions about how television, and stories more broadly, get made.

When it turns out that the police investigating the nail salon’s kidnapping are also part of a television show called Black and White, Impossible Crimes Division with catchphrases such as ‘enhance’, an unnamed ‘tech guy’ and every other cliché you’ve met in detective procedurals we know we’re not in a linear story about missing family and Chinese organised crime.

The sense of artifice is handled perfectly, with clever nods and changes that tell you when something has taken control of Willis’ world and when he’s free to perform unwatched. This sense that everything is watched, that everything is performed is made much darker by the explicit boundaries that say Chinese people don’t get to be cops, that an angry waiter is something to be laughed at rather than empathised with, that urban redevelopment is inevitably for rich White people. It explores racism, sexism and how they impact on the kinds of story we see as acceptable.

When a woman is told she’s not the right fit to lead it’s because she’s a woman and people won’t be interested in her as much as they would be in her tall, handsome and physically strong male partner. It’s presented as the way things are and to push back against them only ever leads to trouble.

What impressed me most was the sense that all these characters are, to some extent, trapped by what the world tells them they’re allowed to be. Breaking free of these expectations isn’t simply a matter of kicking against the pricks but of working at the edges of what’s allowed and pushing little by little.

The anger that this kind of existence provokes in those of us who’ve lived this kind of ‘towing the line’ is palpable on the screen. From Donny Chieng’s incandescent Fatty to Willis’ unattractive and unpleasant treatment of others because he’s simply lost his ability to keep his tone to that those in power expect him to have if he wants to be accepted.

This show is dark because it does not shy away from the fact that so many people are rendered into little more than side characters for others because of the way society at large regards them. The righteously angry educated woman is rejected because she’s too loud, too pushy, too argumentative. The angry person of colour becomes someone who alienates ‘allies’ because they lose their temper, accused of being as bad or worse than those who’ve had their boots upon their heads their entire lives. To say this cut close to the bone for me would be understating it.

It was delicious to see that anger on screen, to see how I’ve so often felt up there in clear tones. I can see this passing by many people, especially those who aren’t used to thinking of themselves as the butt of the joke because they’re ‘good’.

For me it was thrilling to see, especially when combined with explorations of how a show would be scripted, how its tropes deployed and even how its specific words and technical terms would be used to generate meaning.

In some ways the story of Interior Chinatown is a thriller whose mystery is about how the show Interior Chinatown got made, by who and for whom it’s intended.

Meta shows like this can fall over for being too smart for their own good. For me Interior Chinatown works because it has a sense of the story it wants to tell and because, despite all the technical jiggery pokery (technical term there), it has a very clear story – about how we all go about generating meaning in our lives. If you only see the Chinese waiter as there to serve you then you miss so much more. If he only sees you as a customer he too misses worlds.

The show is a deep hearted plea to recognise other people as containing multitudes, to recognise other people as being as equally real as we think ourselves to be, with depths of love and anger, hatred and hope, shame and joy as mysterious to us as we are to them.

Verdict: If the show is a neat procedural thriller on the surface with a scabrous anger underneath, it’s also a deeply sentimental show that sees community, love and family as critical to building meaning. It says these things while showing how relying on meaning being given to/created for us by other people’s stories (from social media or television etc) is an extremely dangerous substitute for that we can build ourselves. Especially when what other people want us to see as meaningful is that difference is to be shunned, that other people are dangers to be guarded against and that family, community and collaboration are the tools of evil.

I can’t say I disagree with those sentiments.

9/10 character archetypes

Stewart Hotston