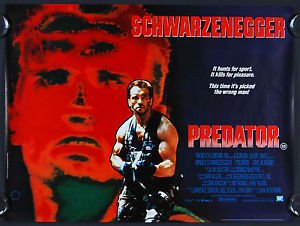

Feature: Predator: The Hunt for The Predator Part 1: Predator (1987)

In the 1980s, action cinema was dominated by big, muscly men, huge explosions and one-liners. And though there were several big name stars active at the time, the king of […]

In the 1980s, action cinema was dominated by big, muscly men, huge explosions and one-liners. And though there were several big name stars active at the time, the king of […]

In the 1980s, action cinema was dominated by big, muscly men, huge explosions and one-liners. And though there were several big name stars active at the time, the king of this crop was undoubtedly Arnold Schwarzenegger. 1987 saw him returning to the role of a special forces soldier, something he’d already explored in the commercial hit Commando, but this time his foe, and his mission, would be very different indeed. With John McTiernan in the director’s chair, Arnold and a cast of equally muscular co-stars would venture deep into the South American jungle in search of the ultimate quarry – a trophy hunter from another world. Would Arnie strike gold with another iconic turn, or would this be a case of just another generic action flick? Greg D. Smith investigates.

In the 1980s, action cinema was dominated by big, muscly men, huge explosions and one-liners. And though there were several big name stars active at the time, the king of this crop was undoubtedly Arnold Schwarzenegger. 1987 saw him returning to the role of a special forces soldier, something he’d already explored in the commercial hit Commando, but this time his foe, and his mission, would be very different indeed. With John McTiernan in the director’s chair, Arnold and a cast of equally muscular co-stars would venture deep into the South American jungle in search of the ultimate quarry – a trophy hunter from another world. Would Arnie strike gold with another iconic turn, or would this be a case of just another generic action flick? Greg D. Smith investigates.When one considers the sprawling franchise for which this initial movie is responsible, it’s quite incredible to consider its origins, and how it could have been so very different. For example, the original inspiration for the movie to be written came from a joke, made after Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky IV, which went along the lines of the character now having fought everyone possible, and that only by placing him in front of an alien could another entry in the franchise be made. From small, weird acorns…

It’s also worth remembering that before Kevin Peter Hall added his unique stature to the role, the Predator itself was supposed to be played by Jean Claude Van Damme, himself a rising star of the time, when the alien was supposed to be more agile and ‘ninja-like’. Various factors saw Van Damme walking away, and the creature got a makeover. Oh, and that distinctive, mandible-filled face that lies beneath the mask? The result of an idle comment from one James Cameron as he sat next to Stan Winston on a flight, the latter passing his time by sketching ideas for the new look creature for McTiernan’s movie.

It’s also worth remembering that before Kevin Peter Hall added his unique stature to the role, the Predator itself was supposed to be played by Jean Claude Van Damme, himself a rising star of the time, when the alien was supposed to be more agile and ‘ninja-like’. Various factors saw Van Damme walking away, and the creature got a makeover. Oh, and that distinctive, mandible-filled face that lies beneath the mask? The result of an idle comment from one James Cameron as he sat next to Stan Winston on a flight, the latter passing his time by sketching ideas for the new look creature for McTiernan’s movie.

At any rate, though it received fairy desultory critical responses upon its release, Predator has gone on to become something of a classic of the genre. Cited by many as one of Schwarzenegger’s best, it gave us his other iconic catchphrase (‘Get to the choppa!’) and proved that there was room in the action genre for more than just straightforward, unapologetic gunfights and explosions. In fact, it may well be one of the finer examples of intelligent action cinema from the period.

Allow me to explain.

First off, let’s look at the dialogue – there really isn’t a lot of it. That’s not to say that it approaches the anaemic scripting for its lead that he had in The Terminator, but the first four minutes of the movie don’t actually involve any speaking at all. Moreover, with one notable exception, there is no pertinent exposition delivered to the audience via dialogue. Our characters, our setup, our antagonist: all are introduced to us and given depth and three-dimensionality by actions – be it the back and forth banter of the team, the way in which a person moves or behaves, or even simple looks. It’s an economical film without taking that economy to any extreme, and it benefits hugely from this.

It also takes its material a lot more seriously than one might expect. Two years prior to this, Arnie was flexing his muscles in Commando as John Matrix, retired special forces superman on a one-man mission to rescue his daughter from a literal army. That film, while it has its merits, is full of cliché and silliness, from hokey dialogue to obvious dummies in FX shots and re-use of explosions. With Predator, we get an entirely different level of commitment – there’s no visible dummies here, no stupid jokes or laughable bad guys, and no disposable enemies for Schwarzenegger’s Dutch to mow his way through single-handed. The original mission of the team, to infiltrate a bandit camp and rescue hostages from a force which outnumbers them several times over, relies on teamwork. Nobody simply runs in, all guns blazing; everyone has their part to play, and crucially, nobody feels expendable.

It also takes its material a lot more seriously than one might expect. Two years prior to this, Arnie was flexing his muscles in Commando as John Matrix, retired special forces superman on a one-man mission to rescue his daughter from a literal army. That film, while it has its merits, is full of cliché and silliness, from hokey dialogue to obvious dummies in FX shots and re-use of explosions. With Predator, we get an entirely different level of commitment – there’s no visible dummies here, no stupid jokes or laughable bad guys, and no disposable enemies for Schwarzenegger’s Dutch to mow his way through single-handed. The original mission of the team, to infiltrate a bandit camp and rescue hostages from a force which outnumbers them several times over, relies on teamwork. Nobody simply runs in, all guns blazing; everyone has their part to play, and crucially, nobody feels expendable.

And for the creature itself, McTiernan takes lessons from the original greats. We don’t actually see a full shot of the Predator until nearly an hour into the film, and even then, the glimpses we get are sparing, right up until the final climactic fight with Dutch. More importantly, keeping with the theme the movie establishes early on, we never get any kind of direct exposition with regards to the Predator, beyond what the team themselves are able to infer as events progress. The feeling of tension, of the unknown out there stalking our protagonists, is one we share because we don’t have any clearer idea than they do. The only glimpses we are afforded which they miss simply confirm the fate of their comrades and the fact that the creature can be hurt. Even the point of view shots, showing us what the Predator sees get around the potential issue of overexposing the alien by the simple expedient of being rendered in ‘thermal’ vision, with distorted audio and only an occasional appearance of alien characters which are not remotely linked to anything to which we can relate. Like the horror films of yore, less is more with the Predator, and we don’t have the luxury of knowing its strengths or weaknesses in any detail, leaving us feeling much as Dutch’s team does – that it may simply wipe all of them out without any chance of comeback.

It’s this visual shorthand employed by McTiernan which – I believe – led to one of the oft-voiced criticisms of the movie at the time of its release: that snazzy effects and big action set pieces made up for an overly simplistic plot. In this, I cannot agree. The setup is straightforward – Dutch’s team is sent on a rescue mission to recover political prisoners from a band of rebels in a hostile area. The actual story is much more nuanced. From the beginning, we are aware that Carl Weathers’ Dillon is an old comrade of Dutch, but now works with the CIA and is involved in darker and less straightforward things than the squad. Early on, an exchange of looks between the General who calls Dutch in and Dillon tells us the audience that something more is going on than Dutch is being briefed about. Throughout the first half of the movie, various exchanges between the two escalate the tension. Dutch suspects – even expects – Dillon to be up to something, and Dillon obviously feels a lot of conflict about his duplicity, regardless of his bluster.

It’s this visual shorthand employed by McTiernan which – I believe – led to one of the oft-voiced criticisms of the movie at the time of its release: that snazzy effects and big action set pieces made up for an overly simplistic plot. In this, I cannot agree. The setup is straightforward – Dutch’s team is sent on a rescue mission to recover political prisoners from a band of rebels in a hostile area. The actual story is much more nuanced. From the beginning, we are aware that Carl Weathers’ Dillon is an old comrade of Dutch, but now works with the CIA and is involved in darker and less straightforward things than the squad. Early on, an exchange of looks between the General who calls Dutch in and Dillon tells us the audience that something more is going on than Dutch is being briefed about. Throughout the first half of the movie, various exchanges between the two escalate the tension. Dutch suspects – even expects – Dillon to be up to something, and Dillon obviously feels a lot of conflict about his duplicity, regardless of his bluster.

As the movie progresses, we learn more about the team and the mission evolves. The initial raid on the rebel encampment reveals what various clues have been pointing to – that Dillon has them on the trail of something entirely other than he has told them. The capture of Anna throws another complication into events – Dutch has no intention of taking someone along who he suspects will betray them to the enemy at the first opportunity, Dillon insists she could be useful.

In keeping with many action movies of the time, especially ones involving Schwarzenegger, Anna is the sole female part, but what is interesting is that the movie specifically avoids her character being a love interest or a femme fatale. Caught in a situation she didn’t sign up for, Anna spends much of her early time with the squad trying to escape them. It’s only when one is literally brutally slaughtered in front of her by the Predator that she seems to relent to staying with them, as much out of a sense of self-preservation as anything else. She never screams, never acts as a damsel in distress, and indeed ends up as one of the only survivors, alongside Dutch. Let’s not pretend that her character represents a landmark moment in female representation on screen, but for the time, she certainly represented a change, and a positive one at that.

This can be extended to the other characters as well. It’s easy to miss how progressive the casting of Predator was for its time – yes we have a white male lead, but alongside him we have two people of colour, two men of native American descent and a Hispanic woman. It’s hardly Black Panther, but at a time when box office blockbusters with almost entirely white casts and other ethnic groups generally relegated to villains or supporting roles were the norm, it bears mentioning that Predator was ahead of the curve.

And on the subject of the team, the other fascinating factor in this movie is that they all get to be actual characters rather than cyphers, each exhibiting particular traits and talents that make them all equally useful and equally important. Mac is the demolitions and traps expert, Billy is the tracker, Blaine is the heavy support guy, Hawkins is the radio and comms expert, Poncho is linguistics and general purpose and Dutch is a strong leader, believing in his men, deferring to them when necessary and never feeling the need to showboat or exert his authority over them. As a point of comparison, take James Cameron’s excellent Aliens – the colonial marine team in that is arguably on a similar mission to Dutch and co, but it’s difficult to pick much more than stereotypes among them. Vasquez the ass-kicking woman; Hicks the capable, unassuming guy who gets to be in charge; Drake the big ugly tough guy; Hudson the competent joker; Apone the ball-busting sergeant. After that it gets vague: Wierzbowski is sort of there, Frost – who knows? It’s perhaps an unfair comparison given that Aliens’ main character is Ripley, and the marines are mainly there to serve as background fodder, but the difference is striking nonetheless, adding to the sense of verisimilitude that Predator carries in the way it addresses its core protagonists. Even now, with a cynic’s eye and a lifetime of watching both fictional and factual stories about the military, there’s never one of those moments in Predator – the ones where I am suddenly moved to exclaim ‘that wouldn’t happen’ or ‘they wouldn’t actually do that’. That’s important, given the fantastical nature of the enemy they find themselves up against.

And on the subject of the team, the other fascinating factor in this movie is that they all get to be actual characters rather than cyphers, each exhibiting particular traits and talents that make them all equally useful and equally important. Mac is the demolitions and traps expert, Billy is the tracker, Blaine is the heavy support guy, Hawkins is the radio and comms expert, Poncho is linguistics and general purpose and Dutch is a strong leader, believing in his men, deferring to them when necessary and never feeling the need to showboat or exert his authority over them. As a point of comparison, take James Cameron’s excellent Aliens – the colonial marine team in that is arguably on a similar mission to Dutch and co, but it’s difficult to pick much more than stereotypes among them. Vasquez the ass-kicking woman; Hicks the capable, unassuming guy who gets to be in charge; Drake the big ugly tough guy; Hudson the competent joker; Apone the ball-busting sergeant. After that it gets vague: Wierzbowski is sort of there, Frost – who knows? It’s perhaps an unfair comparison given that Aliens’ main character is Ripley, and the marines are mainly there to serve as background fodder, but the difference is striking nonetheless, adding to the sense of verisimilitude that Predator carries in the way it addresses its core protagonists. Even now, with a cynic’s eye and a lifetime of watching both fictional and factual stories about the military, there’s never one of those moments in Predator – the ones where I am suddenly moved to exclaim ‘that wouldn’t happen’ or ‘they wouldn’t actually do that’. That’s important, given the fantastical nature of the enemy they find themselves up against.

It’s worth mentioning the gore as well, simply because, although it’s not as action-heavy as people seem to recall, when the action does start (and on a couple of other occasions) Predator gets very graphic. However, there’s a cleverness at play here too. Having introduced us to this squad of tough, uncompromising soldiers who’ve been everywhere and seen everything, the film needs to give us a reason why they would fear what’s out there. Part of this is, as I’ve already addressed, done by keeping our antagonist mysterious and mostly hidden from our heroes, but that alone wouldn’t do it. The finding of what’s left of Green Berets known to Dutch is gruesome, but it serves to start the process of unnerving the soldiers and making them wonder exactly who or what’s out there.

The deaths, as they come, tend to involve short, sharp bursts of extremely graphic violence, which punctuate the relatively sedate pace the movie sets as the team trail through the jungle towards an extraction point it becomes increasingly clear they won’t ever reach. Hawkins is bloodily disposed of before Anna’s eyes before being dragged away, Blaine gets cored where he stands. Mac gets his head literally blown off, Dillon loses an arm before being killed and Poncho suffers the indignity of serious injury by a falling tree followed later by an almost casual headshot. Only Billy actually dies offscreen, though we later see the Predator claim his gruesome trophy from his corpse before casually tossing the rest of it away. It serves to emphasise the powerlessness of these powerful men against the enemy which stalks them, and it works incredibly well.

Scoring all of this action is Alan Silvestri, staple composer for various 80s action movies. His signature is all over the movie, from his militaristic beats to timpani drums and catchy hooks. It helps to drive the movie, each scene underlined by sounds which complement and enhance the onscreen action.

Scoring all of this action is Alan Silvestri, staple composer for various 80s action movies. His signature is all over the movie, from his militaristic beats to timpani drums and catchy hooks. It helps to drive the movie, each scene underlined by sounds which complement and enhance the onscreen action.

By the time the final confrontation begins, it’s possible to argue that the movie becomes a little formulaic. Our final, lone hero must stand alone against the terrible enemy which has claimed his comrades, and somehow win against all odds. It’s a theme as old as time in storytelling generally and one which was and continues to be a staple of the genre. As if recognising this, McTiernan does his best to at least make the journey towards the conclusion we all suspect interesting.

Dutch doesn’t suddenly man up – he’s essentially driven into a corner. He doesn’t discover the beast’s weakness through some clever thinking so much as by blind luck, cowering away from it while covered in mud and realising through observation – as a soldier would – that it cannot see him, and is therefore relying on heat to observe its surroundings. In the chases, we get to see much of the action from the point of view of the Predator, which means we get the higher-pitched, distorted grunts and exclamations from Dutch, sounding weaker and almost pitiful. We get a montage of Dutch setting elaborate traps and making himself a homemade bow which can fire an arrow through a tree, but although he scores some initial hits, it’s clear that he’s still outmatched, and it’s only that a) the Predator elects to fight him face to face, fist to fist and b) sheer blind luck that sees him actually able to defeat his foe. Even as he does, he’s then forced to run away from the final explosion signifying the end of the creature.

It’s probably worthy of note again that at this point the creature laughs maniacally – the same laugh it adopted from Billy, but this time uniquely entirely undistorted. In death, the Predator finally makes a relatable noise, emphasising the very words Dutch uttered earlier in the movie – ‘If it bleeds, we can kill it.’ Not for McTiernan the cheap way out of humanising the alien with a monologue or some sudden appearance of someone to explain him – the movie signals to us that our boogeyman is mortal by the simple use of a laugh.

Our last shot of Dutch is him slumped in the chopper, staring vacantly out at nothing, as a mournful theme plays. There’s no sense of triumph, none of the usual feeling that the good guy won the day, simply that he’s wearily survived, and that even though he has, the experience has changed something fundamental within him. Our hero’s story ends with him not elated, but broken. It’s difficult to imagine a less cliched way for a genre movie of the time to have ended.

Our last shot of Dutch is him slumped in the chopper, staring vacantly out at nothing, as a mournful theme plays. There’s no sense of triumph, none of the usual feeling that the good guy won the day, simply that he’s wearily survived, and that even though he has, the experience has changed something fundamental within him. Our hero’s story ends with him not elated, but broken. It’s difficult to imagine a less cliched way for a genre movie of the time to have ended.

It may not stand in any pantheon of greatest movies ever made, but Predator is a far more elegantly crafted beast than it is often given credit for. From a diverse cast to a deliberate storytelling style, exquisite pacing and a genuine sense of threat shared between audience and protagonists, it may well be the most cerebral example of the genre of its time, and certainly deserves consideration among its more widely elevated peers today. There’s a reason why this one odd little action movie, whose genesis lay in a joke, has enjoyed such lasting appeal, and why it has spawned so many sequels in various formats and indeed continues to do so. It’s definitely a movie that’ll ‘stick around’ for some time to come.