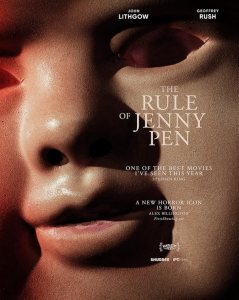

Review: The Rule of Jenny Pen

Starring Geoffrey Rush, John Lithgow, George Henare Directed by James Ashcroft Galaxy Pictures, in cinemas now After a debilitating stroke, a former judge is confined to a rest home where […]

Starring Geoffrey Rush, John Lithgow, George Henare Directed by James Ashcroft Galaxy Pictures, in cinemas now After a debilitating stroke, a former judge is confined to a rest home where […]

Starring Geoffrey Rush, John Lithgow, George Henare

Starring Geoffrey Rush, John Lithgow, George Henare

Directed by James Ashcroft

Galaxy Pictures, in cinemas now

After a debilitating stroke, a former judge is confined to a rest home where he finds himself targeted by a fellow resident.

What is movie horror for? If you are someone who believes that cinematic scares are designed for collective catharsis, where being frightened with fellow mortals in the safety of your local multiplex is, primarily, a form of reassurance, then Kiwi psychological horror The Rule of Jenny Pen is an abject failure. If, however, you’re happy to be reminded of the inescapable terrors of age and infirmity that await all of us who aren’t granted a quick, merciful exit from this life, then James Ashcroft’s movie will scare the living bejesus out of you.

I made the mistake of going to see this on the eve of my 65th birthday. I am (touch wood) reasonably fit for my age and still run 5-10k at least three times a week, so hopefully I won’t end my days, like hapless judge, Stefan (Geoffrey Rush) trapped in a poorly staffed institution persecuted by John Lithgow at his most casually sadistic, via the medium of a tatty, sinister doll complete with empty, glowing eyes.

This is a terrific, genuinely unsettling film, with two superbly pitched performances at its heart. Lithgow is as excellent as you might expect, but this is Rush’s movie. Despite his Oscar win for his portrayal of David Helfgott in Shine nearly thirty years ago, I’ve never been overly excited by Rush’s acting, but Stefan is a difficult, curmudgeonly, bitter, arrogant, lonely man, as keen in his judgements to condemn victims for being victims as he is to lock away their attackers. This undermining of the line between victim and perpetrator is what makes The Rule of Jenny Pen so complex and compelling, and Rush never resorts to moments of easy sympathy. He is a very difficult character to like, which enriches the film by constantly challenging the audience to question where its moral centre lies.

Credit too, to George Henare’s portrayal of retired Māori Rugby star Tony, Stefan’s roommate, caught in the crossfire, and the catalyst for the film’s most affecting emotional moment, which, without words, suggests an acre of untold backstory.

There are hiccups along the way. Director James Ashcroft relies a tad too much on cognitive confusion, which, while true to the character, frustratingly serves to confuse the narrative (and conveniently iron over a few plot holes). This could be a perfect film if it played things a little straighter with the finer details of its storytelling.

Verdict: If you’re getting on in life and worried about your health, or you have a relative in full time care, you might struggle to ‘enjoy’ The Rule of Jenny Pen, but if you want to see another superb example of antipodean horror, then this is a film that will stay with you all year. 8/10

Martin Jameson