2001 A Space Odyssey: Interview: Brian Sanders

British art legend Brian Sanders is celebrating his 80th birthday with an exhibition at the Lever Gallery of selected illustrations from his career – including some of those that he […]

British art legend Brian Sanders is celebrating his 80th birthday with an exhibition at the Lever Gallery of selected illustrations from his career – including some of those that he […]

Brian Sanders knew he wanted to draw “as far back as I remember.” He never wanted to be anything other than an artist “and I’m still trying,” he jokes.

Born in London, he was evacuated during the Second World War to Saffron Walden in Essex – near where he now lives. “My earliest memories are of asking for pencil and paper. My sister, who was five years older than me, used to bribe me with paper during the war when she had to look after me. I always insisted that it mustn’t have lines.

“I don’t know why but I was interested in drawing from the age of four. I do remember wanting to pick up the pencil and draw.

“I was encouraged; you always find wonderful teachers and I fell into them at my junior school here, before I went back to London, and I was given every encouragement. They provided me with the equipment because they could see that I could do it. It was interesting really that they spotted it that early.”

Back in London, “I went to a grammar school at the foot of Tower Bridge, and the art master there was a similar sort of teacher. I had to pretend I wanted to be an architect to get into the school because I don’t think art was ever recognised as being that important. When we were given careers advice and told all the things we could be – doctors, lawyers etc. – the headmaster asked, ‘Is there any subject we haven’t touched upon?’ I said, ‘Commercial art, sir’.

“‘Interesting you should say that, Sanders – had a brother go into commercial art. We just dragged him out in time!” That was the advice I got.

“Having said that, the art master there was superb. He got into talks with the Slade [School of Art] and I could have gone to the Slade had my father not being already supporting my sister through nursing. He didn’t say I couldn’t go, but the onus was on earning some money.”

After a short time working at an advertising agency, Sanders went to work for Artist Partners, an agency that represented around 60 artists. “They had everyone from Tom Eckersley, the great poster artist, right the way through to what I wanted to personally do – I was always interested in figurative illustrations. My education in commercial art came from that: I was a runner for Artist Partners and it’s how I got to meet all those artists.”

In hindsight, Sanders seems not to regret missing the formal training. “I can’t help feeling that going to art school would not have got me where I wanted to be,” he explains. “I wanted to get a living out of drawing, and that’s what I got really. It’s not just what you’ll see at the exhibition – this is a tiny selection of the first 15 years – but I’ve done everything from 50 sets of stamps to large scale paintings of parades in the army. I’ve had a very wide career.”

He was still drawing throughout his National Service, during which he was taken into the Intelligence Section of the Royal Marines. On finishing his compulsory two years in the armed forces, he was devastated to find that his roll of personal drawings had disappeared from his kitbag on the way back to England. “I suspect someone was looking for cigarettes and heaved them overboard,” he says wryly.

But that meant he was back in the UK without a portfolio to show anyone. Luckily, “I knew a photographer called Adrian Flowers who offered me a job. I worked with him for nearly two years while I got my portfolio together.

“Every night I worked on my own illustrations, mainly black and white in those days, and at the end of that period I selected 12 pieces and went freelance. Adrian was very good – he was working in Chelsea where it was all happening, and he gave me a studio within his studio. He didn’t charge me for it, but I paid him back by painting backgrounds and things for him, helping in that way. When I got the work together, Artist Partners said they would actually take me on.”

Sanders wasn’t happy, though, with his own material. “I was leaning heavily on two artists of great repute – David Stone Martin and Ben Shahn – and I couldn’t get away from their way of working. Even though I was becoming quite successful doing that sort of work and earning quite a lot of money, I was a bit ashamed of not doing my own thing and being more or less an imitator. One day I went in to Adrian, took all my specimens and burned them. He must have thought I’d gone mad. I went down to Elephant and Castle to work in a junkyard, just drawing what I saw and making illustrations from them.”

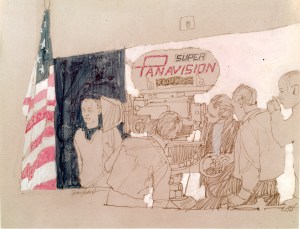

It was through what he did there that he came to the attention of filmmaker Stanley Kubrick. “Stanley had seen some of my work,” Sanders says. “By that time I was working for the three colour supplements that had come out in the 1960s – The Sunday Times, The Observer and The Telegraph – and he asked if he could see other stuff. I was always experimenting and was working with collages. He called me in and asked if I would be interested in drawing while he made a film. He wasn’t keen on my having cameras, but if I really needed a piece of reference, he could arrange that – but if I did use a camera at all, he wanted every negative from it.”

Aware that Kubrick was a photographer himself, and had had problems with photographs of his work being taken surreptitiously, Sanders agreed to the conditions.

“He said there was no point coming down every day, ‘because we don’t change the set every day’ so what was suggested was to go down two days a week, and I would then also work from the material that I got back at my studio. There are a couple of larger pictures that are four foot square. I couldn’t have done those on the spot; I did them back at the studio.”

Kubrick gave Sanders a free hand on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey, not giving any indication of what he wanted the illustrator to capture. “It was an absolute gift of a job, one of the things that very rarely happen to any illustrator – the only brief was to look and do what I wanted with it. That was wonderful. Not many people give you that. If I wanted to draw the lighting man sitting up in the roof I could do that.”

The sets fascinated Sanders. “I was really sucked in on that. I couldn’t think how somebody could produce them,” he recalls, the wonder in his voice still evident half a century later. “What Stanley did was he got people who were actually working in the space industry to design the stuff, people who were already thinking of designing it for reality. It was as simple as that. I was amazed at the amount of research that had gone into it.

“The first large set that I went on was the big centrifuge. That must have been twenty to thirty feet high. It was obviously connected to the lighting system and the first time it went round, everything started to explode – it was really a quite interesting moment.

“I didn’t get to ever work in the miniature bit. I didn’t even know it was going on because Stanley was so cagey about it, and I understand why now! It was amazing.”

Sanders assumed that the illustrations he was doing would be used to interest people in the upcoming movie, but “they were never shown, and in fact I asked Roger Caras who was the main person I was working for, for permission to use two of them for an article on [German, later American rocket scientist] Wernher von Braun. He said yes, so I assumed it was okay. Any publicity was good.”

Kubrick, however, wasn’t happy. “Stanley didn’t blow his cool but he was very cross because he hadn’t been consulted, and when the thing came out, I got a very cool reception from him. I said I did ask permission but Roger hadn’t told him and I took the can back for him. I didn’t fall out with him.”

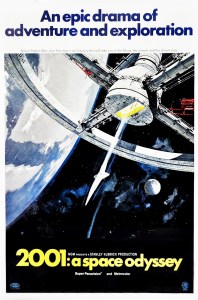

There was only one time that Kubrick and Sanders didn’t see eye to eye. “Stanley asked if I’d like to do the poster for the film. I said yes, and he said he had this idea – which was inside a film cinema theatre looking at the back views of the audience looking up at the Crab Nebula. I said, ‘Stanley, almost anything in your film is a better idea than that’. He said, ‘You don’t want to do it’ and that was it. And I didn’t do it – and I was right because the poster featured shots from the film and better for it.”

Sanders is still full of respect for Kubrick’s foresight. “He thought ahead of everyone – he could see that kids would take to it. My eldest son, who is now in his mid-50s, is a great Kubrick fan – he thinks it’s extraordinary. It came out at at time when he was ready for it. I said to Stanley that I didn’t understand the end of the film, and he said, ‘but your children will’, and he was right, absolutely right.”

He also has a lot of time for Kubrick the person. “He was smashing – my eldest son was knocked over in the street when I was working on it, and Stanley sent a whole pile of toys. He was very generous in that way, even though he didn’t know him.”

Sanders didn’t work with Kubrick again, although their paths crossed in later life. “He turned up at a party – we had mutual friends in North London – and bummed a fag off me. He wasn’t meant to be smoking, and said, ‘just one’. That was the last time I met him.”

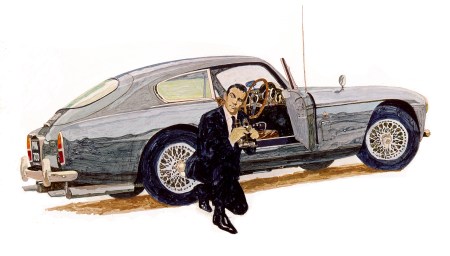

Although he loves science fiction and is currently reading the works of J.G. Ballard, Sanders didn’t do much else in that field throughout his career. He was asked to illustrate a series called Cars in Fiction, and drew Sean Connery as James Bond alongside an Aston Martin – but used the correct version, the DB III, from Ian Fleming’s novel Goldfinger, rather than the DB5 in the movie. “The DB III was mine, the one in the illustration,” he notes. “The reason I used Connery was because for me he was James Bond and he’s never been replaced in my mind.”

The exhibition includes the colour pictures of his work with Kubrick, although other images can be found on his blogspot The Art of Brian Sanders (http://artofbriansanders.blogspot.co.uk/). His recall of that time is crystal clear “because it was so original. It’s not hard to place myself back there at the time. It’s still one of the highlights of my career.”

Images courtesy of Brian Sanders; thanks to Erin Lumley for her help in arranging this interview