Interview: Dave Gibbons: How Comics Work

From DC Thompson to DC Comics, Dave Gibbons has worked his way up the comics ranks, starting as a speech balloon letterer to being the one-man creator that he is […]

From DC Thompson to DC Comics, Dave Gibbons has worked his way up the comics ranks, starting as a speech balloon letterer to being the one-man creator that he is […]

From DC Thompson to DC Comics, Dave Gibbons has worked his way up the comics ranks, starting as a speech balloon letterer to being the one-man creator that he is today. Dave is comics royalty and he took time out from his busy schedule to talk about his new book – How Comics Work – which he co-wrote with Tim Pilcher. Looking at the different aspects of how a comic is put together, the book is generously illustrated with Dave’s creations from 2000AD and Doctor Who Weekly onwards. Nick Joy was there to talk all things digital, Watchmen and Meep the Beep.

From DC Thompson to DC Comics, Dave Gibbons has worked his way up the comics ranks, starting as a speech balloon letterer to being the one-man creator that he is today. Dave is comics royalty and he took time out from his busy schedule to talk about his new book – How Comics Work – which he co-wrote with Tim Pilcher. Looking at the different aspects of how a comic is put together, the book is generously illustrated with Dave’s creations from 2000AD and Doctor Who Weekly onwards. Nick Joy was there to talk all things digital, Watchmen and Meep the Beep.

I’ve just finished an advance copy of your new book How Comics Work and more than anything I hadn’t realised how much I didn’t know about the end-to-end process. I imagine this book was produced in response to the same questions you keep getting from fans wanting to break into the industry? And is this the sort of book you’d have loved to have existed at the start of your career?

I’d have loved this book at the beginning of my career. In fact at many stages throughout my career, and even up to the present day, I still buy lots of books on process, anatomy, how to draw, and pictorial composition. Never having been to art school I’ve always got the suspicion that there’s one vital thing that I’ve never learnt and I find in most books on drawing and comics you find something you haven’t come across before – hopefully that will be the case with this book. Perhaps there’s also a lot of stuff [in the book] that’s original to the way I’ve found my way around, which initially was by literally looking over people’s shoulders and asking working practitioners how the job is done.

In his new book about the creation of 2000AD, Pat Mills talks about the awful way that writers, artists and creators were treated in the 70s, leading to many working abroad. Was that a key turning point for you? Do creators get a better deal today?

In his new book about the creation of 2000AD, Pat Mills talks about the awful way that writers, artists and creators were treated in the 70s, leading to many working abroad. Was that a key turning point for you? Do creators get a better deal today?

When I was starting out I was grateful for any deal, and in Britain IPC and DC Thompson – or Fleetway as they were known then – were the only game in town. They didn’t pay particularly well, they held on to your artwork, and they didn’t give you royalties or any participation in the success of what you’d worked on. They wouldn’t even let you sign your work, so it was a really raw deal. When the Americans came over, particularly the guys from DC, and offered us all those things, added to the fact that it had always really been my ambition to work in American comics, it was a complete no-brainer.

So, yes, it was a turning point for me. Creators generally do get a better deal today – even the people who publish 2000AD now give reprint money and there’s always the possibility of royalties. Certainly a lot of the American writers and artists get much much better deals than we ever had, and I think it gets much better as we go along. In a way, we’re all standing on the shoulders of the generation before.

Is it harder to break into the industry today, or do you think it has always been a tough one to crack?

I think it’s probably harder today because there are less comics and less little niches for people to do their learning work. When I did a lot of work for DC Thompson it wasn’t very well paid, there was never any deadline rush and they would give you extensive notes on how to improve the drawing to tell the story better. That was the way that I broke in, also doing balloon lettering where I would get artwork for a few days to keep and study. And there were things in 2000AD – Future Shocks – which were 3 or 4-page stories that they would use to try out new writers and artists. Those don’t really exist today. On the other hand it’s much easier to be in touch with fellow fans and collaborators and publishers all across the world because of the internet and for that reason easier to get your work seen no matter where you live. It used to be that you had to live near New York or London or Dundee. It’s swings and roundabouts really.

As a child I used to pick up books about how to draw the Marvel or DC way, but I knew I wasn’t great at drawing and was far better at writing. What I like about your book is that it’s very inclusive – if you can’t draw, write. There’s many different threads to comic creation.

As a child I used to pick up books about how to draw the Marvel or DC way, but I knew I wasn’t great at drawing and was far better at writing. What I like about your book is that it’s very inclusive – if you can’t draw, write. There’s many different threads to comic creation.

Yes, and I’ve done most of them. I’ve done lettering, colouring, pencilling, inking, writing – so I’ve always had an overall view of the whole thing. I always wanted to both write and draw my work. When I was growing up I had no idea that there were separate writers and artists, let alone separate letterers and colourists, so since then I’ve always been aware of all the different facets. Really, what comics are all about is storytelling, and If you can’t tell stories in pictures you may be able to write stories. There are some good books out there these days on how to write for comics… and hopefully this will be one of them.

How did working with Tim Pilcher shape the book? Was he good at being subjective and helping you clarify what you were talking about?

It was great to work with Tim – we’ve been friends for a long time. The way we worked is that he had a road map of what he wanted to be in the book and he’d talk to me on the phone, on Skype or in person, and he’d ask me lots of really quite informed questions. Tim knows a lot about the production of comics and then he’d boil down the things I had to say.

It was a very good way to work because he made me explore corners that I might not have otherwise clarified. He was also involved in picking the artwork examples, and again I probably would have picked more pretty ones and not so many of the really raw ones which showed me drawing not particularly well. But I think that it’s a fairly impartial and honest look at what the preliminary stages look like.

Lettering is for me one of the most neglected aspects of comic production. Poor text can derail a comic and yet it is so often taken for granted. There’s a chapter on lettering in the book – do you think this might surprise some people? I particularly like your Funky Gibbons font!

Lettering is for me one of the most neglected aspects of comic production. Poor text can derail a comic and yet it is so often taken for granted. There’s a chapter on lettering in the book – do you think this might surprise some people? I particularly like your Funky Gibbons font!

It’s been said that lettering is like the soundtrack on a movie. If it’s right, you never notice it, but if it’s bad you really do notice it. It does add a lot to the presentation of the page and good lettering can really make or break the way that the story is told and the way that the book looks. Of course, now with computer fonts – and I’m pleased you like the Funky Gibbons font – it’s become much less… aha… monkey work, because you don’t have to rule out lines, you merely type it in on the computer. But you still have to be aware of the design and the placement of the balloons. It’s still a very skilled and precise part of the procedure.

I’ve seen some of Alan Moore’s incredibly-detailed scripts for Watchmen. I just wondered whether something so precise runs the risk of stemming the artist’s creativity or actually presents interesting challenges for you. Not that I consider Watchmen to be anything less than perfect!

That’s good. I wish I did! Alan would basically give me lots of options but then it would be up to me to choose which option to go with and to actually simplify, or clarify, or reduce often very complicated ideas to ones that could be expressed on the comic book page. On the other hand I’ve worked with scripts that had very little description and they’re both challenging in their own way.

I prefer working full script to the so-called Marvel Method where you work from a plot and then the dialogue is added afterwards. Other than that I’m perfectly happy with any kind of script. It can be very demoralising to have to spend weeks drawing something that you know the writer has just tossed off in an afternoon, but if you’re lucky enough to work with good collaborators then that generally isn’t the case.

Prior to reading this book I’d never considered the concept of character sheets – that you specifically design the various aspects of the character’s body and face in different poses. Is this a luxury you don’t often have on a project?

Prior to reading this book I’d never considered the concept of character sheets – that you specifically design the various aspects of the character’s body and face in different poses. Is this a luxury you don’t often have on a project?

If you’re going to be drawing something very brief then you’re only going to have draw the characters a few times anyway. But if you’re going to have to draw them a lot then it’s very helpful to have a character sheet. The idea comes from animation where various people are all drawing the same character, and you need a way to reduce it to simple repeatable geometric shapes shapes. So even if it was a fairly short project I’d always probably do some kind of brief impression of all the characters and important things that I had to draw.

Your training as a building surveyor led you to design some very intricate cityscapes in Watchmen. Is mastering 3-point perspective the greatest challenge with building design?

Technically, it’s not part of building design. In the world of architecture it is a separate skill – the person who will take a plan and turn it into a three-dimension. I think the fact I understand how buildings go together makes it easier for me to draw them because I know how big a door is, how wide a street is, and so on. Nowadays there’s software that will figure out the perspective for you, but if you know how to do it the hard way, you can tell the computer what to do.

You were named the first Comics Laureate in 2014 – congratulations.

You were named the first Comics Laureate in 2014 – congratulations.

Thanks

How important was it for you to see that the comicbook art form was now getting public recognition in this way? It felt like a kick in the teeth to the elite – a lot of my generation owe our literacy more to comics than books.

The idea of the Comics Laureate was to celebrate and support comics in school. I’ve always been a big advocate of the benefits of reading comics and when I actually spoke to school teachers and school librarians they well all very much on side. They were of a much later generation than mine and were actually quite accepting of comic books. They were not so much asking ‘Should we have comics in schools?’ as ‘Which ones do you recommend?’ So that was quite enlightening for me. And I also got to work with the Oxford University Press, preparing a line of graphic texts – as they called them – specifically aimed at different levels of comprehension and ages of reading. There were also plans for class participation on reading graphic texts, which I found really inspiring. The Comics Laureate is now being fronted by Charlie Adlard (The Walking Dead) and I think it’s still a very worthwhile thing, even though the doors aren’t as locked as we thought they were.

In the book, you mention many of your influences and heroes – Harry Harrison, Jack Kirby, Frank Hampton, Wally Wood. You’re now an influence to a whole new generation of artists. If you were dispassionately appraising/critiquing your style, why do you think people like it? Or is that something you can’t objectively see?

In the book, you mention many of your influences and heroes – Harry Harrison, Jack Kirby, Frank Hampton, Wally Wood. You’re now an influence to a whole new generation of artists. If you were dispassionately appraising/critiquing your style, why do you think people like it? Or is that something you can’t objectively see?

I’ve always been interested in telling the story, and that’s always been the main thing to me; all the artists that you mention were actually dedicated to that. That’s what I learned from them and what I try to pass on. I’ve got no particular desire in showing-off how well or badly I can draw, I just want to tell the story. That means you need situations that are exciting and characters that are empathetic. People can read the emotions; that’s the sort of thing people respond to – it’s certainly what I respond to. Forget about the artist and just get involved in the characters in the story. As to how well or badly I do it is indeed something that I can’t objectively see.

The world of digital art is featured frequently in your book – I just wondered whether it was something you resisted for some time or whether you were an early adopter? Instant blocks of black and no more ink smudges or running out of ink mid-stroke!

I’ve always been interested in technology and its application in the real world to help people do things. Clearly there are lots of things the computer does that are very helpful in the production end of comics – sizing pages, rolling panels and setting up perspective, doing colouring and adding letters. I’ve been using computers in comics for 25 years and obviously as time has gone on they’ve become more artist-friendly and quicker. I’ve always embraced the latest iterations of software and technology with glee. There is a problem that you can let the computer do too much stuff for you, and that’s the advantage of also knowing how to do it old school. You should use the computer as a tool rather than something that dictates the way you work or how something looks.

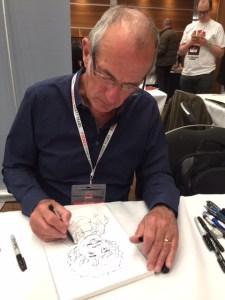

I met you briefly at the 2000AD convention earlier this year and you seemed pleased with my request for a sketch of Tom Baker’s Doctor Who instead of what looked like a long line of fans wanting Rorschach, Dan Dare or Rogue Trooper sketches. Do you ever tire of drawing these favourite characters?

No, I’m quite happy to… perform. Obviously I draw a lot of Rorschach but then he’s so simple to draw, particularly with the practice I’ve had. It’s when you have to draw something with a bit of finesse to it that it becomes difficult to draw it under those circus conditions. Particularly drawing attractive women, because you’ve only got to add one line too many or get an eye or a nose slightly wrong and you’ve not got the effect you wanted. I prefer to draw in a fairly blunt, dark pen, which is fine for craggy people, but if you want a bit of delicacy… that can be difficult.

In his book on how to write, Ray Bradbury explains simply that to get good you have to write every day, whether it’s a short story or a diary entry. Is it the same with your drawing – do you need to keep exercising those muscles?

Yes, I think you really do, and I don’t do as much of that now as I used to. I used to be drawing for hours and hours every day because I had to. It’s good to keep the muscles flexed and it does take a little while if you haven’t drawn for a bit to get back into the drawing. I do life drawings as well, which are very informative, so it’s good to draw things that aren’t going to be seen. I’ve also found that it’s good to work under a bit of pressure, because that makes you much more economical and effective in what you do choose to draw. Certainly I wouldn’t argue with Ray Bradbury!

If someone were to come up to you and say that as a consequence of reading your book they now had a comic book in the works, would you consider this as job done?

If you can inspire someone else to get involved and enjoy making comics, then that’s great. I’ve had a lot of pleasure both professionally, and before that as an amateur, telling my stories in pictures. It’s not for everybody, and not everybody can write or draw. It’s a particular kind of skill and set of requirements to be an artist or writer. I’m always thrilled when somebody shows me something that I’ve inspired them to do.

Where do you stand in the colourisation of black-and-white strips? For example, I’ve seen the recent reprints of your old Doctor Who strips and they just don’t feel the same, possibly because you already had the shading in there already.

Where do you stand in the colourisation of black-and-white strips? For example, I’ve seen the recent reprints of your old Doctor Who strips and they just don’t feel the same, possibly because you already had the shading in there already.

You obviously draw in a different way for black-and-white rather than colour and you do put a lot more black in there. You tend to add more texture which can often get lost when the colour is added to it. On the other hand, I think you can go too much the other way and there are some modern comics that rely on the colourist to actually make sense of the drawing. I try and draw somewhere between the two.

I think also the kind of colouring you do makes a difference. If you do a lot of modulation in the original black-and-white drawing, the colour is best approached in a fairly simple and flat way. I don’t think doing more is necessarily adding more.

Finally, my first exposure to your work was the afore-mentioned Doctor Who Weekly and I was quite upset when Beep the Meep’s true identity was revealed – complete with devilish eyes and jagged teeth. Thank you for that nightmare!

The Meep was one of my favourite things I ever worked on. Pure Pat Mills black humour and a great character to draw. He is a character that lodges in a lot of people’s memories. It was great that we were able to tell the story in such a way that it came as a genuine shock when he bared his teeth and pulled his blaster out of his furry, little pouch. I’m glad you appreciated it!

The Meep was one of my favourite things I ever worked on. Pure Pat Mills black humour and a great character to draw. He is a character that lodges in a lot of people’s memories. It was great that we were able to tell the story in such a way that it came as a genuine shock when he bared his teeth and pulled his blaster out of his furry, little pouch. I’m glad you appreciated it!

How Comics Work by Dave Gibbons and Tim Pilcher is released September 21st by Rotovision Books and you can read our review here

Thanks to Graham Robson for his help in arranging this interview.