Quatermass: Interview: Toby Hadoke

Toby Hadoke’s long gestating book on Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment is published on 12 May by Ten Acre Films, covering every aspect of the “thriller in six parts” that […]

Toby Hadoke’s long gestating book on Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment is published on 12 May by Ten Acre Films, covering every aspect of the “thriller in six parts” that […]

Toby Hadoke’s long gestating book on Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment is published on 12 May by Ten Acre Films, covering every aspect of the “thriller in six parts” that had such an enormous effect on British television drama. Paul Simpson caught up with Hadoke to discuss the good professor’s first TV outing – and much more…

Toby Hadoke’s long gestating book on Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment is published on 12 May by Ten Acre Films, covering every aspect of the “thriller in six parts” that had such an enormous effect on British television drama. Paul Simpson caught up with Hadoke to discuss the good professor’s first TV outing – and much more…What is it about the concept of Quatermass that has haunted you for so long?

Well, obviously I was a Doctor Who fan and I was disinclined to like anything else. But Quatermass had always been spoken of in hallowed terms. I do remember [the 1979 Quatermass] even though I was only five or six – I have images of Land Rovers and double-barrelled shotguns. I’ve always liked that post apocalyptic, dystopian stuff of people surviving in Arran jumpers as humanity starts to fray, as you turn the water off, as it were.

My family were inclined to rib me about my Doctor Who obsession. If you’re the youngest and you’re as obsessed as I am, I suppose I was ripe for lampooning.

My family were inclined to rib me about my Doctor Who obsession. If you’re the youngest and you’re as obsessed as I am, I suppose I was ripe for lampooning.

But Quatermass always escaped that. We had an A to Z of Monsters with an entry for Quatermass. Whenever Quatermass was spoken about it was almost in hushed tones. It was from the olden days and I’ve always been drawn to that sort of thing.

I used to find silent movies haunting, not just because of the slightly different speed that people moved. It was like slight parodies of humanity because it [showed] people but they moved a bit quicker, they looked a bit different and they acted slightly different – and that to me was almost spookier than seeing a monster, because it’s human but not quite. But also, the knowledge that they were real people who lived and breathed; you see them for that moment on the screen but they’ve had a whole life leading up to that, that was gone by the time their flickering images reached me. That idea of capturing people, in this video age we’re very blasé about, but sometimes those fragments would be all that existed of a whole life; I found that ghostly and haunting and weird.

Quatermass had a bit of that with it because it was from the ancient days of the 1950s, and for me in 1986, I was surprised anyone was still alive. It didn’t help that all three Quatermasses were dead as well as a couple of the other actors that you read about, so you assumed that everyone else had gone, and actually over time, you discover that that wasn’t the case. But the idea was that it was made by people who’d died, that this was a time before even Doctor Who. And of course television developed at such a pace in the 50s and 60s that the personnel and the methodology were almost unrecognisable from one decade to the next.

Quatermass had a bit of that with it because it was from the ancient days of the 1950s, and for me in 1986, I was surprised anyone was still alive. It didn’t help that all three Quatermasses were dead as well as a couple of the other actors that you read about, so you assumed that everyone else had gone, and actually over time, you discover that that wasn’t the case. But the idea was that it was made by people who’d died, that this was a time before even Doctor Who. And of course television developed at such a pace in the 50s and 60s that the personnel and the methodology were almost unrecognisable from one decade to the next.

It’s sad now that when I say to people that I’m writing a Quatermass book, I have to explain what Quatermass is. When I told people when I was fifteen in the 1980s that I was “writing a Quatermass book”, I didn’t have to explain what it was to anybody. It was part of our race memory, if you like. So the fact that it had persevered and etched itself into the consciousness of everybody meant I respected it before I saw it.

It’s sad now that when I say to people that I’m writing a Quatermass book, I have to explain what Quatermass is. When I told people when I was fifteen in the 1980s that I was “writing a Quatermass book”, I didn’t have to explain what it was to anybody. It was part of our race memory, if you like. So the fact that it had persevered and etched itself into the consciousness of everybody meant I respected it before I saw it.

When I was fifteen or so, a friend of mine lent me the video of Quatermass and the Pit. I’d expected to make concessions because Doctor Who’s Revenge of the Cybermen wasn’t as good as I’d imagined it from reading the Target book. I’d seen other old stuff by this point that had not quite matched up to my expectations but Quatermass absolutely did.

When I was fifteen or so, a friend of mine lent me the video of Quatermass and the Pit. I’d expected to make concessions because Doctor Who’s Revenge of the Cybermen wasn’t as good as I’d imagined it from reading the Target book. I’d seen other old stuff by this point that had not quite matched up to my expectations but Quatermass absolutely did.

I was astonished at what a big production it was. Let’s not forget, these were high end productions and [producer] Rudolph Cartier always pushed for much more money. So if you’re used to watching videotaped studio bound science fiction from the 60s – obviously not the ITC film series but anything made in a studio – and then you watch Quatermass, you see the number of characters and the scale and the ambition of the film sequences. They were bigger than I thought – and then add the sophistication of the storytelling and all the wonderful things we know about Nigel Kneale… I was blown away.

And then, one of those moments also happened. I’d heard talk of the gravel moving [as Sladden collapses in the churchyard]. My mum walked in when I was watching that scene for the first time and she said, ‘Oh God, I remember this, the gravel starts to move.’ I hadn’t necessarily known that ‘the gravel moving’ was Quatermass, it was a thing that people talked about. I’d heard Mum talk about Doomwatch and things like that, so there was other stuff that I knew that they’d seen that was the mythical sci-fi of the past. I was thinking, ‘Yes, she remembers the gravel moving in this’ but it would be a massive coincidence if this thing that I was watching had been the thing that she remembered so I said, ‘Yeah, it might have been this one or it might have been Doomwatch or one of the other ones.’ And then literally, at that moment, Richard Shaw hits the ground and the gravel starts to move…

And then, one of those moments also happened. I’d heard talk of the gravel moving [as Sladden collapses in the churchyard]. My mum walked in when I was watching that scene for the first time and she said, ‘Oh God, I remember this, the gravel starts to move.’ I hadn’t necessarily known that ‘the gravel moving’ was Quatermass, it was a thing that people talked about. I’d heard Mum talk about Doomwatch and things like that, so there was other stuff that I knew that they’d seen that was the mythical sci-fi of the past. I was thinking, ‘Yes, she remembers the gravel moving in this’ but it would be a massive coincidence if this thing that I was watching had been the thing that she remembered so I said, ‘Yeah, it might have been this one or it might have been Doomwatch or one of the other ones.’ And then literally, at that moment, Richard Shaw hits the ground and the gravel starts to move…

I just thought, what a moment for us to have, but also, that speaks to what Quatermass is about. It’s about race memories, it’s about common fears that we all share that can spread panic and haunt us, and it happened when I was watching the show. And my mum’s not one to talk about sci-fi or popular culture or anything like that, so the fact that also it had penetrated her in a way made it seem extra special as well.

I just thought, what a moment for us to have, but also, that speaks to what Quatermass is about. It’s about race memories, it’s about common fears that we all share that can spread panic and haunt us, and it happened when I was watching the show. And my mum’s not one to talk about sci-fi or popular culture or anything like that, so the fact that also it had penetrated her in a way made it seem extra special as well.

So, it’s always had that lustre and having got it, I watched The Pit over and over and over again, to the extent that I could at one point have probably performed it for you line for line.

And I started writing to the actors and they started writing back and the rest is history. But quite a long history with a lot of procrastination!

And I started writing to the actors and they started writing back and the rest is history. But quite a long history with a lot of procrastination!

Were you writing to them just for your own edification?

I think, certainly when I wrote to them, I said I wanted to write a book. I lived in the countryside in the middle of nowhere, I didn’t have any contacts or anything but I’ve always been a ‘nothing ventured, nothing gained’ guy. That said, I’ve always had the pessimism of ‘I’ll try but I’ll probably fail.’ I’m not one of those people who strides in and goes ‘We’re gonna make this deal happen!’ So I’ll expect failure but I’ll still aim high!

I thought the least I will do is have a lovely folder of letters from actors. The first actor I wrote to was Richard Shaw because I was so taken with his performance as Sladden in Quatermass and the Pit, especially as he’s quite ordinary in his Doctor Whos [The Space Museum, Frontier in Space and Underworld] and yet I think in Quatermass and the Pit, it’s an extremely sophisticated, timeless and really good performance that sort of really anchors the piece. The piece would not be anything like as strong without his contribution. He wrote me a lovely letter back.

Then a friend of mine, Roger Clark, very kindly bought from a car boot sale an Actors and Artists Yearbook from 1985. He said, ‘Is this useful to you because I know you like writing to actors?’ And so, it was just whichever agents had listed their actors in that. If they’d got a Quatermass actor, I would write to the actor, care of the agent. It had Richard Shaw, it had Isabel Dean, it had a few others. In those days I couldn’t look up people on IMDB, so you didn’t know if people were alive. The only clue you had to whether people were alive was if there was a copy of Quinlan’s Character Actors in the W.H. Smiths you happened to be perusing. But according to that book, I thought Duncan Lamont was still alive even though he died in 1979. I was still looking for him until I found out from an interview with John Abineri that he’d died.

Then a friend of mine, Roger Clark, very kindly bought from a car boot sale an Actors and Artists Yearbook from 1985. He said, ‘Is this useful to you because I know you like writing to actors?’ And so, it was just whichever agents had listed their actors in that. If they’d got a Quatermass actor, I would write to the actor, care of the agent. It had Richard Shaw, it had Isabel Dean, it had a few others. In those days I couldn’t look up people on IMDB, so you didn’t know if people were alive. The only clue you had to whether people were alive was if there was a copy of Quinlan’s Character Actors in the W.H. Smiths you happened to be perusing. But according to that book, I thought Duncan Lamont was still alive even though he died in 1979. I was still looking for him until I found out from an interview with John Abineri that he’d died.

So even if people were still alive or not was not information you had to hand. I gradually started finding other ways of getting in touch with people but quite often it would be through other means. I remember Janet Burnell, who plays the interviewer in the first episode of Quatermass and the Pit, turned up in an episode of Brush Strokes, so I was like, ‘Right, she’s still alive, I’ll write to her.’ It was so annoying: I’ve since discovered that there were some actors who’d maybe stopped acting or just hadn’t been in programmes who were still alive until 2005 who I could have written to, but I didn’t have a system… but I was pretty lucky.

So even if people were still alive or not was not information you had to hand. I gradually started finding other ways of getting in touch with people but quite often it would be through other means. I remember Janet Burnell, who plays the interviewer in the first episode of Quatermass and the Pit, turned up in an episode of Brush Strokes, so I was like, ‘Right, she’s still alive, I’ll write to her.’ It was so annoying: I’ve since discovered that there were some actors who’d maybe stopped acting or just hadn’t been in programmes who were still alive until 2005 who I could have written to, but I didn’t have a system… but I was pretty lucky.

All the Quatermasses were dead but I’ve got everyone who’s got second billing in a serial. So Isabel Dean [Judith Caroon] from Quatermass Experiment, we kept in touch for a long time and Monica Grey [Paula Quatermass – right] from Quatermass II and Cecil Linder [Roney – above with André Morell] from Quatermass and the Pit. But then, having done the actors, I thought I should do the production people, so I wrote to Jack Kine and Bernard Wilkie, care of the BBC Special Effects Department, which resulted in a phone call from Matt Irvine, that bloke off Swap Shop.

All the Quatermasses were dead but I’ve got everyone who’s got second billing in a serial. So Isabel Dean [Judith Caroon] from Quatermass Experiment, we kept in touch for a long time and Monica Grey [Paula Quatermass – right] from Quatermass II and Cecil Linder [Roney – above with André Morell] from Quatermass and the Pit. But then, having done the actors, I thought I should do the production people, so I wrote to Jack Kine and Bernard Wilkie, care of the BBC Special Effects Department, which resulted in a phone call from Matt Irvine, that bloke off Swap Shop.

Then I thought I’d write to Peter Cushing about Nineteen Eighty Four and I knew that Who’s Who had home addresses in it because I’d flicked through a copy in the school library. So flicking through to look for Peter Cushing, I happened upon Rudolph Cartier who I assumed was dead because I hadn’t seen his name on credits. I assumed he was probably 100 when he made it – but there he was and his home address was there. So I wrote to him and he phoned me up, and he then put me in touch with a couple of actors he was still in touch with. I think he told me that Clifford Hatts, the designer of Quatermass and the Pit, was in the London telephone directory so I wrote to him and he sent me all sorts of goodies.

Trial and error: some people didn’t write back, some people did and wrote back amazing things. Some people I didn’t write to at all because I didn’t know they were still alive and only discovered it when it was too late.

Trial and error: some people didn’t write back, some people did and wrote back amazing things. Some people I didn’t write to at all because I didn’t know they were still alive and only discovered it when it was too late.

I acquired a lot of stuff and I sent book breakdowns to BBC Books and a couple of other people who said, ‘There’s no market for this.’ And what I would have written in the early 90s would have been a bit like some of those early books on The Prisoner probably: synopses, lists of characters and obviously the quotes from the letters and stuff, which was the gold dust, to me. But obviously in recent years I’ve been able to go to the BBC Written Archive.

In a way it’s a good thing I’ve taken so long because when I did The Road for the BBC, [Nigel Kneale’s widow] Judith Kerr came along. I’d written to her a couple of times and not heard anything back. So I plucked up the courage to speak to her and she was lovely. She made her own way to the recording and she was so delighted that The Road was being done, she invited me for dinner. I went to their house, I touched the monster that was in a plastic bag in the corner, she showed me Nigel Kneale’s office.

In a way it’s a good thing I’ve taken so long because when I did The Road for the BBC, [Nigel Kneale’s widow] Judith Kerr came along. I’d written to her a couple of times and not heard anything back. So I plucked up the courage to speak to her and she was lovely. She made her own way to the recording and she was so delighted that The Road was being done, she invited me for dinner. I went to their house, I touched the monster that was in a plastic bag in the corner, she showed me Nigel Kneale’s office.

I was in touch with the family and I did something for them when Judith died; they asked me for a couple of favours and I was helpful, as one tries to be. I think they were quite sympathetic to what I’m trying to do with the legacy of their dad so they’ve let me have access to everything.

I was in touch with the family and I did something for them when Judith died; they asked me for a couple of favours and I was helpful, as one tries to be. I think they were quite sympathetic to what I’m trying to do with the legacy of their dad so they’ve let me have access to everything.

I’ve now got what remains of Nigel Kneale’s scripts and paperwork, and everything that was in the house when Judith died has come to me. I’ve got loads of material that wouldn’t have been in the book and the book would have been poorer for it, had I done it even five years ago. So yes, it’s been quite a journey.

So were you thinking of it just as one book at that point?

Yes, definitely just the one book.

Yes, definitely just the one book.

Then I think because I got so much on the first three serials, we were thinking of splitting it into two but at that point I was quite keen to get a book out to sell at the Alexandra Palace performance of The Quatermass Experiment Live, which was September 2023. [Publisher] Stuart [Manning] said ‘Well, why don’t you just do a book on Experiment and a book on II and a book on Pit… then a book on the films and then a book on everything else?’

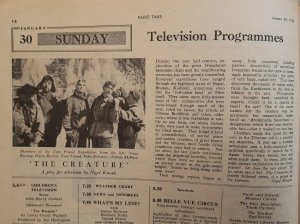

That brought with it an advantage because I’d had to drop the chapters on 1984 and The Creature, which I think are important developments with that team, which can now go in the Quatermass II book because there’s a big gap in the paperwork with Quatermass II. So I can’t write some of the stuff about that, that I’ve written about Experiment and Pit.

That brought with it an advantage because I’d had to drop the chapters on 1984 and The Creature, which I think are important developments with that team, which can now go in the Quatermass II book because there’s a big gap in the paperwork with Quatermass II. So I can’t write some of the stuff about that, that I’ve written about Experiment and Pit.

I think there’s some interesting stuff to be said about 1984; less about The Creature because there’s no production file or anything but there’s enough. They’re an important part of the patchwork, if you like. Then the book wasn’t ready, neither one of us was ready to get it out for the live performance. I’m quite pleased at the end of the day because I wouldn’t want to be wanging about with books whilst trying to revel in that wonderful occasion… and here we are now, finally.

In your research, interviews and everything is there something that you found out that changed your perspective on Quatermass?

I found loads of stuff about the development of the serial that I didn’t know and that I would have to say therefore, at the moment, nobody knows.

I found loads of stuff about the development of the serial that I didn’t know and that I would have to say therefore, at the moment, nobody knows.

Looking at how Kneale developed it is really interesting because Quatermass isn’t the main character originally. He introduces this old scientist as he’s storylining it because he needs an ending: he needs to kill his monster and then when he’s found a reason to do that, he has this old scientist character who he then feeds back into the beginning of the story… and he gradually takes over as the main character.

He’s originally called Professor Charleton. It seems to be that was always going to be a placeholder and then he looks through the telephone directory – and he has lots of lovely letters from Quatermasses saying ‘Why did you choose the name?’ And he writes back to all of them and it’s really sweet.

Is the telephone directory story true?

Yes.

Bearing in mind we all know the other infamous telephone directory story…

That’s very true. No, it seems they thought a Q sound would be a good place to start and they had a look and they went ‘Oh yeah, that’s the one.’ He wanted a name that would stand out but without being wacky. It’s an entirely serious endeavour in that sense.

And also, just for a spoken thing, it’s got the half syllable, it’s got the sibilance, there are so many ways you can say it, angrily or happily or whatever.

It’s genius. I mean, the choice of name is so key to its success. It’s extraordinary that a decision like that could have such resonance but we wouldn’t be talking about “Charleton” in such hushed tones, would we? So, looking at what we could have had, of course it would have been well written and the characters would have been great, but Kneale makes so many smart decisions away from what he originally planned. It all contributes to the serial we have at the end, so it’s all useful storytelling processes that he goes through in order to alight upon what we finally get. But the conclusion was supposed to be, the monster was supposed to talk and that’s the reason that the Professor is introduced…

It’s genius. I mean, the choice of name is so key to its success. It’s extraordinary that a decision like that could have such resonance but we wouldn’t be talking about “Charleton” in such hushed tones, would we? So, looking at what we could have had, of course it would have been well written and the characters would have been great, but Kneale makes so many smart decisions away from what he originally planned. It all contributes to the serial we have at the end, so it’s all useful storytelling processes that he goes through in order to alight upon what we finally get. But the conclusion was supposed to be, the monster was supposed to talk and that’s the reason that the Professor is introduced…

There’s this stuff about absorption: the creature absorbs information, it absorbs matter in order to acclimate to our atmosphere and temperature and environment in order to propagate itself. It’s got a burgeoning intelligence as well, or it’s got an intelligence but it needs to articulate its intelligence so it needs to assimilate intelligence in the same way it’s assimilated biology. It demands, on live television, an Einstein brain and that is why the scientist is brought in because it wants to absorb him in order to absorb his intelligence. That’s the genesis of Quatermass.

But that provides a different ending to the one we get but also I think key is that at some point Kneale goes, ‘I think it’s probably better if the monster doesn’t talk.’ And I think, thank goodness. There’s something about the nebulous nature of the Quatermass threats. I know you have the zombie guards in Quatermass II but they are still avatars…

But that provides a different ending to the one we get but also I think key is that at some point Kneale goes, ‘I think it’s probably better if the monster doesn’t talk.’ And I think, thank goodness. There’s something about the nebulous nature of the Quatermass threats. I know you have the zombie guards in Quatermass II but they are still avatars…

They’re minions.

Yes, you don’t speak to the emperor blob or anything like that. That means that Quatermass isn’t battling some malignant force that dreams of power, he’s dealing with biological entities that just happen to be different to us and dangerous to us but don’t necessarily have any cognizance of being agin us, if you like. It’s more, they’re almost unfeeling. I love that description of the creature in the first one, of being a plankton of the ether. It just seeps, the spaceship just encounters it and it goes ‘Oh.’ Like a culture would, it grows, it does what it does. It would either grow on something or in this case it digests the astronauts and reassimilates them in order to acclimate to us, but it’s a biological process rather than a cognisant one of a thirst for conquest, if you like.

Yes, you don’t speak to the emperor blob or anything like that. That means that Quatermass isn’t battling some malignant force that dreams of power, he’s dealing with biological entities that just happen to be different to us and dangerous to us but don’t necessarily have any cognizance of being agin us, if you like. It’s more, they’re almost unfeeling. I love that description of the creature in the first one, of being a plankton of the ether. It just seeps, the spaceship just encounters it and it goes ‘Oh.’ Like a culture would, it grows, it does what it does. It would either grow on something or in this case it digests the astronauts and reassimilates them in order to acclimate to us, but it’s a biological process rather than a cognisant one of a thirst for conquest, if you like.

In Kneale’s novel of The Quatermass Conclusion, there’s something about Quatermass knowing that he is dealing with forces that actually have no idea who he is, if I recall correctly.

In Kneale’s novel of The Quatermass Conclusion, there’s something about Quatermass knowing that he is dealing with forces that actually have no idea who he is, if I recall correctly.

Yes, that’s it. There’s that brilliant bit in the last one where he says they’re sucking up these youths probably because it tastes nice or even just to give them a slight thrill or a slight jolt. It’s nothing; it’s the same way we might pluck a bit of honeysuckle and suck the little bit. He goes to the effort of describing getting musk from a deer: you get the tiniest bit but to do that you have to slay the whole animal – and it’s as trivial as that. And to that creature all the way out there in space, we are nothing. We’re like a speck of dust on the floor – and that of course is quite depressing, in a way, because we’re nothing, but that does then focus on how important individually and humanity is because, in that great cosmic landscape, that’s kind of all we’ve got that’s of any value because we can’t compete with anything else, in a sense.

It’s talked of as being grim and doom-laden but obviously the climax of The Quatermass Experiment is an appeal to the humanity that resides within the creature. For all that we are tiny specks and not very important, the rejoinder to that is that ultimately small, beautiful things is what life is all about. Actually clinging onto your humanity is all you can do in the face of this, because everything is cataclysmic change. Kneale is writing in the 1950s where everything is changing and change is not a destruction free process. Change is renewal, does often actually mean breaking old things.

So, I think Kneale’s not dour in that sense – actually what he thinks about the importance of humanity within all of this grim often unfeeling universe, there’s almost a religious aspect to it and when he’s planning his stories, particularly the first one, he is thinking in religious terms. When they’re trying to get Caroon’s memories back he does talk about seances and exorcisms. Quatermass is basically in the pulpit in Westminster Abbey at the end going, ‘All we’ve got is our souls.’ He’s appealing to the souls of the people.

So, I think Kneale’s not dour in that sense – actually what he thinks about the importance of humanity within all of this grim often unfeeling universe, there’s almost a religious aspect to it and when he’s planning his stories, particularly the first one, he is thinking in religious terms. When they’re trying to get Caroon’s memories back he does talk about seances and exorcisms. Quatermass is basically in the pulpit in Westminster Abbey at the end going, ‘All we’ve got is our souls.’ He’s appealing to the souls of the people.

Which is in a sense, the same in II and Pit as well.

Yes and I think that’s partially again because you don’t really have conversations with the bad guys about their differing views. It’s not like talking to Davros about his advocacy of eugenics and Nazism and the different moral viewpoints. It’s almost as if the creatures in Quatermass don’t really have a moral viewpoint, in that sense. It’s not an exercise… although, I am going to backtrack on that now because of course the Martians are sort of Nazis but their Nazism comes from a biological purpose, in that they’re insects who have a thing about ridding the hive of mutations which is an evolutionary drive.

Yes and I think that’s partially again because you don’t really have conversations with the bad guys about their differing views. It’s not like talking to Davros about his advocacy of eugenics and Nazism and the different moral viewpoints. It’s almost as if the creatures in Quatermass don’t really have a moral viewpoint, in that sense. It’s not an exercise… although, I am going to backtrack on that now because of course the Martians are sort of Nazis but their Nazism comes from a biological purpose, in that they’re insects who have a thing about ridding the hive of mutations which is an evolutionary drive.

It’s an instinct.

It’s an instinct.

Yes, what we see in nature. He’s trying to rationalise the irrationality of Nazi views, if you like, by going, “what if they’re basically based on insects and black magic?” which is just genius.

It’s so rich this stuff, it’s so fertile, it’s so smart and it deserves so much more than to be consigned to lists of cult programmes, because it wasn’t a cult, it was mainstream dramatic television. Yes, of course we know how much science fiction has been influenced by it but in terms of what those productions did for television, those tendrils reached out further than just science fiction. And it’s astonishing, watching how television changed between each of the three productions too. You watch television evolve before your eyes.

So, what is the book? Is it a particular sort of history of it? Or is it, “All you ever wanted to know about The Quatermass Experiment but were afraid to ask”?

Hopefully, it’s got a bit of everything. There’s a chapter on Nigel Kneale, but I only go up to 1960 because I will do the rest of him later on. I interviewed Judith Kerr, I’ve interviewed his children, I’ve interviewed his brother, who I don’t think has done an interview about him before, who was really useful. I’m looking at Nigel Kneale’s background and influences and him growing up, and in that chapter, looking at some of his other work as well. It’s a sort of life and times of Nigel Kneale. Fortunately a lot of the actors in Quatermass were also actors with him when he was an actor at Stratford, so there’s stories there that cross reference.

Hopefully, it’s got a bit of everything. There’s a chapter on Nigel Kneale, but I only go up to 1960 because I will do the rest of him later on. I interviewed Judith Kerr, I’ve interviewed his children, I’ve interviewed his brother, who I don’t think has done an interview about him before, who was really useful. I’m looking at Nigel Kneale’s background and influences and him growing up, and in that chapter, looking at some of his other work as well. It’s a sort of life and times of Nigel Kneale. Fortunately a lot of the actors in Quatermass were also actors with him when he was an actor at Stratford, so there’s stories there that cross reference.

Then there’s a look at his development of The Quatermass Experiment, so everything you need to know from that first idea, when he does a few lines to break down each episode, to the various synopses that he does, to then what we see.

Then there’s a look at his development of The Quatermass Experiment, so everything you need to know from that first idea, when he does a few lines to break down each episode, to the various synopses that he does, to then what we see.

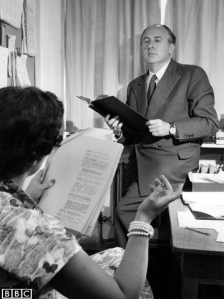

And then what we see: there’s a production diary, anecdotes and memories from the cast and crew, contemporary newspaper reports and interviews. I’ve dived into every archive possible. There’s a bit of analysis because why not talk about why this stuff is so rich, and also because it’s a book by me. There’s a chapter on Reginald Tate because I think each Quatermass deserves their day in the sun. There will be a chapter on Rudolph Cartier [right] but that’s going to be in the book on Quatermass II.

And because it’s a book written by me – and I’m so pleased that Stuart allowed me to do this because I feared I might be told it’s a little too much – I’ve done a chapter about every single credited member of the cast. There are details about when they’re cast, what they’ve done before, how they got the part etc. and then at the end there’s a chapter saying what happened to everybody afterwards. I like writing about actors so that’s what I’ve done! And I’m satisfied I’ve found out about everyone apart from maybe two or three who’ve fallen off the radar and have very common names. I spent a lot of work on that chapter and I don’t know if it will interest people but it interests me.

I’m pleased that I’ve been able to do that because looking at the actors looks at the history of what people did, what was around, what people were making and the fact that people live interesting lives before and after. There’s a brilliant fact about Ian Colin who plays Detective Inspector Lomax that is also related to a famous monster but I’ll save that for the book. I spoke to the woman Paul Whitsun-Jones [James Fullalove] was married to at the time, got some really good stuff there, to Joyce Best and to his son Adam Whitsun-Jones.

I’m pleased that I’ve been able to do that because looking at the actors looks at the history of what people did, what was around, what people were making and the fact that people live interesting lives before and after. There’s a brilliant fact about Ian Colin who plays Detective Inspector Lomax that is also related to a famous monster but I’ll save that for the book. I spoke to the woman Paul Whitsun-Jones [James Fullalove] was married to at the time, got some really good stuff there, to Joyce Best and to his son Adam Whitsun-Jones.

I’ve probably missed something obvious but I like to think, even if you think you know Quatermass pretty well, there’ll be a lot in here that will highlight and illuminate.

We must remember that Quatermass was popular culture so I wanted a book that was as easy to read as watching television is to watch.