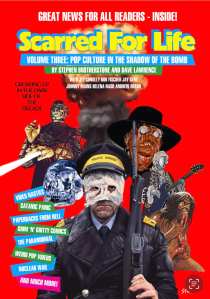

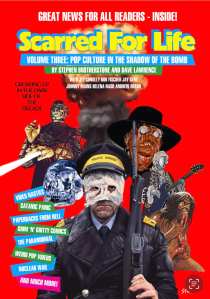

by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence

by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence

scarredforlifebooks.com

It’s been nearly four long and, for many, harrowing years since Volume Two of this trilogy brought us a feast of televisual delights of the 1980s. That volume specifically swerved some content in order to place it in proper context here, and that context is of course The Cold War and the horrors of a potential nuclear war.

This book is broadly split into two sections. The first two-thirds is broadly generalist, concerning itself with similar topics to the first volume, which examined the 1970s. The final third concentrates on material that specifically dealt with, or was informed by, the Cold War and “the bomb”, a peculiar expression whose singular nature rather downplayed the fact that there were, and sadly still are, an awful lot of them ready to be deployed at a moment’s notice. The decision to separate the chapters like this is a wise move, much of this is grim reading by its very nature and having a frothier first part avoids having the whole book become a major downer. That’s no criticism of the work, it’s a reflection of what was happening politically and culturally at the time and there’s no avoiding it. As before, each section begins with an overview which is then followed by detailed examinations of specific media, often including personal experiences from the time by the authors and a number of guest contributors.

On that note, I shall hand over to Sci-Fi Bulletin’s resident gore aficionado Nick Joy to have a gander at films…

Nick: The section on films understandably has ‘Video Nasties’ taking centre stage, and those of us who lived through this period will relate to the authors’ tales of dodgy Italian horror movies, the cassettes often being of dubious parentage (watching some nth generation copies was akin to trying to work out what was happening in a snow storm). The quality of the movies was a moot point, and the writers here tap in to the joy of discovering hidden treasure or forbidden fruit. Oh, and I have seen King Frat, and you really didn’t miss anything.

Andy: While I’ve zero tolerance for “video nasties” I did enjoy reading up on the BBFC’s issues with Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and that brief period when Disney went very weird indeed. Something for everyone here.

Next up it’s Games of the board, paper & dice and pixelated varieties. The Christian Fundamentalist backlash against Dungeons & Dragons gets a superb examination here. It’s an extraordinary story and a prime example of how specific bits of media can be used to shoulder the blame for familial and/or societal failings. It almost makes you laugh considering how mainstream D&D has become, especially with the recent spike in interest due to things like Stranger Things, the very entertaining film and the hugely unexpected critical and commercial success of computer game Baldur’s Gate 3. It was an almost uniquely American backlash of course, for me it was what all the cool kids (I insist on telling myself) did in their lunch breaks for a couple of years. Curiously, and I’m surprised I didn’t know this, the makers of D&D did somewhat capitulate and the 2nd Edition ruleset removed a lot of the demonological aspects of the game.

There’s also plenty to please board game enthusiasts. I distinctly remember the outcry over Waddington’s Bombshell, a somewhat comical game involving diffusing an unexploded bomb which was released in the immediate aftermath of the tragic death of a bomb disposal officer killed in Oxford Street. It’s also fascinating reading up on the various Titanic-inspired games and realising that this was a time when that disaster was still in living memory for anyone in their mid-seventies or older.

Computer games get a look in – most of these are sex-based and are horrifyingly bad and tasteless, none moreso than the egregious Custer’s Last Stand which beggars belief, especially as it was released for the ubiquitous Atari gaming system. I can’t even bring myself to describe it to you, it’s just so horrible. We had an Atari 800 computer, miles ahead in power and graphic quality compared to the likes of the ZX Spectrum, but we didn’t have any filth for it, sadly, not even the one where you get to see Samantha Fox’s pixelated knockers should you manage to win a game of poker (try convincing a young person today that that was a thing, then tell them about how pub peanuts used to work!). The most scarring incident involving our computer was walking in on my mum playing Shamus and hearing her effing and blinding her head off as she tried to avoid being caught by the baddies. I was horrified she even knew such words.

Back to Nick…

Nick: The section on the type of paperback horror nasties served up by the likes of Guy N Smith and Shaun Hutson provides some juicy synopses of the awful (in both senses of the word) prose available to those who weren’t old enough to watch such atrocities but were ok to read about them. In the wake of Garth Marenghi’s skilful pisstaking it’s hard to take this purple prose seriously, but there’s a fine overview of the genre, including big hitters like Stephen King.

The spotlight on British comics understandably holds 2000AD as the torchbearer, and its impact cannot be denied, but there’s also affectionate reminiscences of lesser-known but fondly-remembered weekly comics like Doomlord, Eagle and Scream, the latter being cancelled after a mere 15 issues.

Andy: I loved the revived Eagle comic, Doomlord put the willies right up me and is long overdue a reprint. Next up is American comics of the era, with a particularly good look at DC’s attempt to grow up a bit in the aftermath of their ill-fated DC Explosion of 1978. The whole section generally avoids the well-trodden ground of the most obvious comics, such as The Dark Knight Returns or Watchmen (although Alan Moore’s work is included in the British comics section) and looks at some lesser-known examples. The piece on The Teen Titans, one of my go-to comics at the time, is particularly eye-opening.

The Eighties saw an explosion of mainstream interest in the paranormal, most notably with the TV series Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World and its follow ups. This interest bled out from somewhat po-faced documentaries and entered into the world of fictional TV, with the likes of The Dukes of Hazzard, Miami Vice and most famously The Colbys happily including alien visitations in their storylines. Along with this we have a look at the frankly extremely disturbing magazine partwork The Unexplained. The first issue alone gave us not only photographs of what remained after cases of Spontaneous Human Combustion but a flexidisc of recordings of purported ghosts – I lasted about five seconds listening to this and only made it past the first few issues before it all became too much for me (I’m not alone, author Stephen Brotherstone lasted a mere three issues, the lightweight!).

Finally, for this part of the book, we look at pop music and I was surprised by just how much of this I was familiar with, despite never being particularly interested then as now. It’s easy to forget in these days of everyone living in their own curated cultural bubbles how we all lived in the same cultural bubble back then. With just three, then four, TV channels and not a whole lot more mainstream radio choices we were all exposed to more or less the same stuff. There’s a lot here about the rise of the pop video, and I distinctly remember the fuss and excitement around Michael Jackson’s Thriller video which gets a decent write-up here – it really was a game-changer for what television could do for music, even if MTV’s impact wasn’t as great here in the UK as it was in the USA, at least until the following decade when satellite TV took off.

As discussed, the final part of the book, around 200 of its 740 pages, deals directly with what we might call Nuclear Material. It follows the same format as the first part with sections on films, games, books etc but these are all works dealing specifically with that most grim of subjects. We have heavy-hitters such as Raymond Briggs’ When the Wind Blows (both the book and the film adaptation are covered) and the BBC’s notorious Threads, as well as its previously unscreened 1965 precursor The War Game which finally aired twenty years later, as well as plenty of lesser-known examples which also took a look at The Bomb. I’ve never seen, or read, most of these examples – reading about them is distressing enough – probably only Whoops Apocalypse and the episode of Only Fools and Horses (The Russians Are Coming) entered my purview, and in both cases a little while later when they hit VHS.

Despite being roughly the same age as the authors, my memory of the era just doesn’t feature a lot of Cold War anxiety beyond news reports of CND marches – I wonder if such things were kept from me? We certainly didn’t have any discussion of how to survive a nuclear attack in school, and I never saw the infamous Protect and Survive pamphlet. I have to say that reading this stuff makes me glad I somehow swerved all that anxiety. I do want to see Threads, but much like the similarly unseen Schindler’s List or the Holocaust documentary Alfred Hitchcock advised on, when am I ever, ever going to be in the mood? I think for now I’ll just stick with this and dodge the nightmares.

The book concludes by dipping its toes into the 1990s with a detailed look at the BBC’s faux-live event Ghostwatch (in fact a pre-recorded drama) which, for the authors, marks the end of the Scarred for Life era. They do however have a quick look at some notable examples from later still, especially from children’s television. Although they have confirmed there will be no Volume 4 there are other projects in the works, including an annual, which I look forward to finding under my Christmas tree at some point.

Verdict: The final part of what has been a quite extraordinary achievement. Like the previous volumes this will bring back happy (or not so happy!) memories if you were there at the time, or have you seeking out thrills and scares you missed out on if you weren’t. 9/10

Andy Smith and Nick Joy

by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence

by Stephen Brotherstone and Dave Lawrence